“The ten-dollar founding father without a father,

Got a lot farther by working a lot harder,

By being a lot smarter,

By being a self-starter.”

John Laurens on Alexander Hamilton, Hamilton

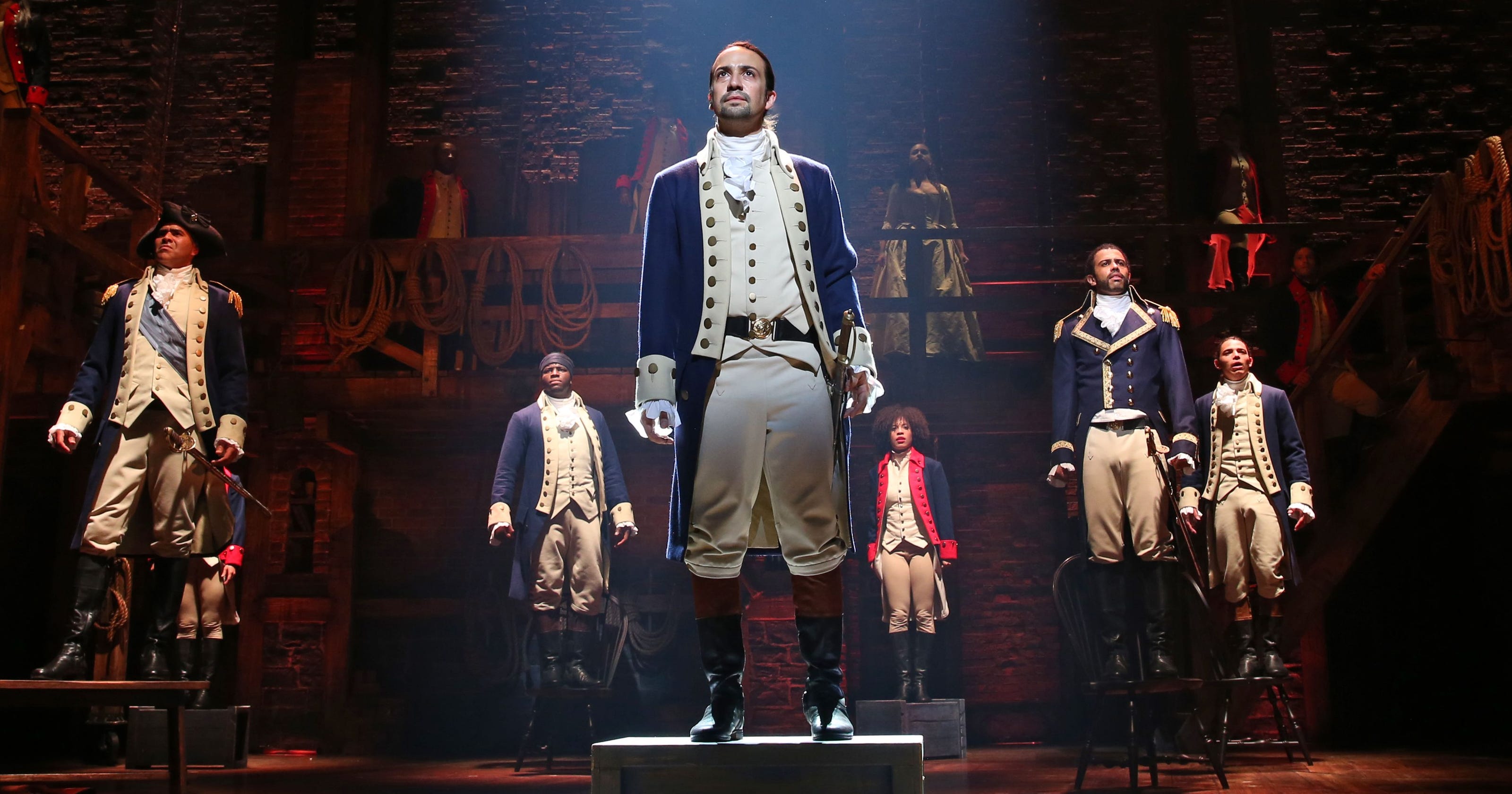

Seven years ago at the White House, Lin-Manuel Miranda described the premise of his still unfinished musical. And an esteemed crowd laughed.

Miranda explained that he’d be performing a song from his project “about the life of someone who embodies hip hop.” Standing on a stage in the storied East Room—where the 1964 Civil Rights Act was signed, where Gerald Ford took the presidential oath of office—Miranda had to improvise, “You laugh, but it’s true…” The gathered glitterati thought “Alexander Hamilton” was a punch line.

Miranda is now revered. He’s on the cover of Rolling Stone. He won a MacArthur “genius” grant. His production, Hamilton, won a Grammy and a Pulitzer. Sunday it won 11 of the 16 Tony awards for which it was nominated. But before all of that, there was the White-House laugh.

But so it goes with virtually every big idea worth having. As Einstein said, “If at first the idea is not absurd, then there is no hope for it.” Had it been obvious, someone else would’ve come up with it ages earlier. But the first-blush appearance of absurdity places an enormous burden on the progenitor. Twain was right: “The man with a new idea is a crank until the idea succeeds.”

This requires not just courage but self-efficacy: this idea might be important—critics be damned—and I can make it so. This is Hamilton’s story: Something breathtakingly inspired and completely implausible but absolutely indefatigable. He was a once-in-a-generation talent but family dysfunction, illness, geography, and more conspired against him. But he was relentless—a natural entrepreneur “ready to beg, steal, borrow, or barter,” an autodidact “reading every treatise on the shelf.”

It’s not hard to see why Hamilton’s story resonated with Miranda. Both prolific writers: the former of innumerable essays; the latter of this 20,000-word musical magnum opus. Both possessing a preternatural spark of creativity; Hamilton conjuring magic on the battlefield, at the Constitutional Convention, in federal service; Miranda seeing before everyone else that the personalities and backgrounds of the Founding Fathers and their internecine war of ideas and words fit perfectly with the history and ethos of hip hop. But Miranda, the son of a Puerto Rican immigrant, also showed Hamilton-esque doggedness. Years and years of struggle preceded his first production’s Broadway arrival and the completion of his meticulous tour de force.

It’s no coincidence that the biggest artists in hip hop—on whom Hamilton’s characters are fastidiously based—exemplify this same blend of talent and resilience. Though they might’ve grown up in the toughest circumstance, they didn’t allow those factors to stop them from working to realize their potential.

For much of America’s history, we saw struggle and success as two sides of a single coin. We assumed an individual’s triumphs followed a long list of trials. Our fellow citizens endured the grueling colonial and pioneer periods; revolutionary, civil, and world wars; slavery, indentured servitude, sweatshops, the Depression. Our nation’s narratives taught that exertion and victory were inseparable. Whether the American Dream, bootstrapping, Horatio Alger-ism, or Frederick Jackson Turner’s “frontier thesis,” our story was that anyone willing to tirelessly strive had access to endless possibilities.

But this part of the American narrative is in jeopardy. Whether it’s because of growing economic inequality, our economy’s continuing anemia, obstacles to upward mobility, our flailing federal government, or something else, more people doubt that personal agency produces success.

Our national ambivalence is exemplified by the tension between those seeking to unmask “privilege” and those advocating “grit.” The former argues that unearned advantages associated with race, gender, family income, and other factors account for much of an individual’s success. The latter argues that learnable personal behaviors are key. At issue is the extent to which effort matters.

I believe the “privilege” lens can be like a candle used for illumination: It reveals dark corners, helping us see the meaningful advantages and disadvantages people possess through no credit or fault of their own. But the privilege candle can also be used for arson, to burn down what others have built through labor. By attributing too much of one’s success to luck, it can diminish her effort and sacrifice. Worse, it can undermine our collective interest in inculcating in our students values (like conscientiousness, verve, and determination) that lead to individual, community, and national flourishing.

This is where our schools come in. They should have a point of view on the essential question, “What contributes to success?” That is, what should our kids believe about the relative weights of the social determinism of “privilege” and the aspirational possibilities of “grit”?

Every teenager will face obstacles. He might be Alexander Hamilton, the “bastard, orphan son of a whore and a Scotsman, dropped in the middle of a forgotten spot in the Caribbean by providence impoverished, in squalor.” He might be Tupac (on whom Miranda modeled his Hamilton), thinking, “Is life worth living? Should I blast myself? I’m tired of being poor, and, even worse, I’m black. My stomach hurts so I’m looking for a purse to snatch.”

What we think about responding to adversity says a lot about our vision of America. If we believe our nation and the next generation is, like Hamilton’s self-assessment, “a diamond in the rough, a shiny piece of coal, trying to reach my goal,” we should proudly instill a sense of endless striving.

Because even after all the privilege is owned, and all of the haters’ laughter subsides, there will still be a distance between where we are and where we want to be. Do we imply to the next generation that there’s only so much they can do, or do we teach them the lessons of the American Dream and Hamilton’s anthem:

“I’m just like my country.

I’m young, scrappy, and hungry.

And I’m not throwing away my shot.”

INTERVIEW | IQ

As a part of Teach Across America, Nicole Baker-Fulgham taught 5th grade in crime and gang ridden Compton, California. That experience inspired Nicole to found The Expectations Project, an organization that believes that the academic achievement gap in U.S. public education can be closed in our lifetimes, but only if people of faith open their hearts, roll up their sleeves, and get to work on behalf of students.

A Detroit native, Nicole has written two books: Educating All God’s Children and Schools in Crisis and has appeared on CNN and ABC. Christianity Today named her one of, 50 Women Leaders Influencing the Church and Culture.

Here is what we want you to wrestle with today: Grit is more than talent, IQ, or any of the other determining factors most individuals associate with success.

Alexander Hamilton’s story personifies grit. Alexander Hamilton was born out of wedlock in 1757 in Nevis, British West Indies. Soon after birth, his mother and father moved with the young Hamilton to St. Croix in the Virgin Islands. Hamilton’s father abandoned the family shortly thereafter. Because Hamilton’s parents were never legally married, the Church of England denied him membership and education in the church school, and he was educated at home by his mother. When Hamilton was 13, Hamilton’s mother contracted a fever and died, leaving Hamilton an orphan. Hamilton was adopted briefly by a cousin, but the cousin committed suicide, again leaving Hamilton an orphan.

He was adopted as a teenager by a Nevis merchant, and worked as a clerk in a store that traded with New England.

While working as a clerk, he became an avid reader and developed an interest in writing. He wrote an essay published in a local newspaper about a destructive hurricane that impressed and caught the attention of community leaders, who decided to collect a fund to send Hamilton to the North American colonies to further his education. In the North American colonies, Hamilton was attending Kings College in New York (now Columbia University), when the American Revolutionary War began. At the start of the war, he organized an artillery company and was chosen as its captain. His abilities and talent were quickly noticed by General George Washington, the American Commander-in-Chief.

Hamilton, a born out of wedlock immigrant orphan, soon became a member of Washington’s inner circle, rising to Washington’s Chief of Staff. As Washington’s closest confidant, Hamilton penned many of General Washington’s messages. After the war, Hamilton was appointed by New York to serve in the Congress of the Confederation. Hamilton was an active participant at the Philadelphia convention for a new constitution and helped achieve ratification by writing 51 of the 85 “Federalist Papers” which supported the new constitution and to this day is the single most important source for U.S. constitutional interpretation.

In the new government under President George Washington, Hamilton was appointed the Secretary of the Treasury, where he organized and founded the new nation’s financial system and established the U.S. Mint. He also established the Cutter Revenue Service (now the U.S. Coast Guard). He later also founded the first American political party (the Federalist party), and founded the Bank of New York.

In 1804, Vice President Aaron Burr took offense to some of Hamilton’s comments, and Burr challenged him to a duel at the same site where Hamilton’s eldest son had died in a duel three years earlier. Burr mortally wounded Hamilton, who died the next day.

The story of the orphan from the West Indies who overcame all odds to shape and inspire a newborn America is told in the record-setting eleven Tony Awards-winning (including Best Musical), 2016 Grammy Award for Best Musical Theater Album and the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for Drama Broadway musical Hamilton.

Wrestle with these questions:

- What do you think makes a leader special? Why are they so dogged in their pursuits of achievement? Is it privilege, or is it grit?

- Some experts think talent originates from one’s natural ability, while others are convinced it originates by being a “striver”. Which of these describes you best? What parts of leadership are from natural talent or striving?

- Grit can change as a function of the cultural era in which we grow up, or grit can increase as one ages. Where in your life have you seen grit change? Is it a result of culture or age?

- What do you think is the relationship between passion and interest?

By your endurance you will gain your lives.

Luke 21:19 ESV