The sun hangs low in the late afternoon sky. It’s Oct. 14, 1964. National Olympic Stadium, Tokyo. The runners toe the line for the 10,000-meter race.

“Boom, the gun goes off,” recalls Billy Mills, one of the many runners in the race.

Billy’s 26 years old — an officer in the Marine Corps with a wife and child.

He wears a crew cut and sports a blue USA singlet over white shorts.

This race supposedly belongs to Ron Clarke, an Australian who holds a world record in this event.

An announcer puts it plain about Billy’s chances: “Billy Mills of the United States is in there — a man no one expects to win this particular event.”

Billy Mills was born on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, located inside South Dakota, a part of the Oglala Lakota (Sioux) nation. He lived the generational poverty familiar to all on Pine Ridge. His mother died when he was 8. His father died when he was 12.

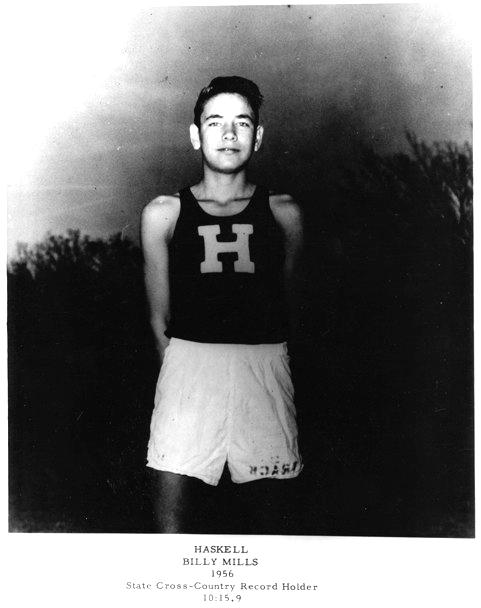

Billy arrived at the University of Kansas in 1958 on an athletic scholarship. Billy was successful on the track. During college, he ran to multiple All-American finishes in cross-country.

At one of those national meets, Billy got ready for the post-race photo with his fellow All-Americans. He thought of his parents and how proud they’d be.

“Then I heard one photographer,” Billy recalls. ” ‘You. Yeah, you — the darker-skinned one. I want you out of the photo.’ And that just went to the depths of my soul, and it just — it broke me.”

He went back to his hotel near Louisville. Later that day…

“I’m on a chair. I open the window — and it took years for me to share this, because I thought it was weakness, I thought it was cowardly,” Billy says. “I’m on the chair. You don’t want to kill yourself. I just wanted to go where it was quiet. I looked out of the window and three-and-a-half or so floors down to the ground and then a little slope. And my thoughts were: ‘It’ll all be over.’ But then I didn’t jump.

“I didn’t jump, because I didn’t hear through my ears — underneath my skin, through energy, an unspoken word, which sounded like, ‘Don’t.’ And the fourth time, so gentle, so loving, but so commanding, like an echo: ‘Don’t.’ And it sounded like my dad’s voice.

“I’m crying. I step off the chair. I’m thinking about what he told me when, three years after my mom died and then before he died, he would tell me that it takes a dream to heal broken souls.

“I got off the chair crying, and I wrote down a dream to heal a broken soul: gold medal, Olympic 10,000-meter run.”

Back on campus a week or so after that night in the hotel room, a beautiful young woman caught Billy’s eye.

“I turned and I followed her — I don’t know if you’d call that stalking or not — and we eventually met,” Billy says. “I fell in love right away, and eventually she fell in love. And, as I shared my stories and my struggles and my fears but my dreams with her, she became this incredible support system. I supported her dreams, she supported my dreams, and my life slowly started to change around.”

Billy and Patricia Mills got married as college seniors.

Tokyo, Oct. 14, 1964: It’s halfway through the 25-lap Olympic race, and Billy is shocking everyone. He’s with the leaders. He runs close to his fastest 5km time ever, but there’s still another 5km to go. Twelve-and-a-half laps. It’s a punishing pace.

“I came so close to quitting,” Billy says. “I looked into the infield. If there was nobody there that recognized me, I was gonna quit. Everybody was local Japanese officials. Anywhere was a great place to quit. I looked into the stadium. Who did I focus on? My wife. She’s crying. And there’s no way I could quit. We made a commitment together.”

The stadium lights go on. Darkness descends. The 10,000-meter race is one of attrition. It’s the longest race in track and field. An American had never won it. As the laps pass, Billy is with the leaders, including world record holder Ron Clarke of Australia. They surge periodically. The pack thins.

“About a mile to go, Clarke made a move,” Billy recalls. “It came so close to breaking me. I said I had to cover it now. I covered the move. I took the lead, slowed it just a fraction. Clarke took lead again, but I recovered. Two laps to go. Clarke looked back. I thought, ‘My God. He’s worried.’ “

Billy joined the Marine Corps in 1962, but he didn’t stop running. And in the year leading up the 1964 Olympics, Billy got a commission from the Marine Corps to focus on training while at Camp Pendleton. There, he got a new coach.

“Tommy Thompson Sr., formerly the coach at the Naval Academy, Canadian, gold medalist in the high hurdles,” Billy says. “He came up to me and said, ‘Son,’ so gentle. ‘I’m so glad you’re here. You have a lot of talent. Now, I’m not gonna coach you. More importantly, I want to be your mentor, but you have to let me inside. You have to let me know your dreams.’

“And he tapped his heart. ‘You’ve gotta let me inside of your heart.’

“I thought, ‘My gosh, this is like my dad speaking to me. This is like God sending my dad’s spirit to me through Tommy Thompson Sr.’ I opened up my heart to him.”

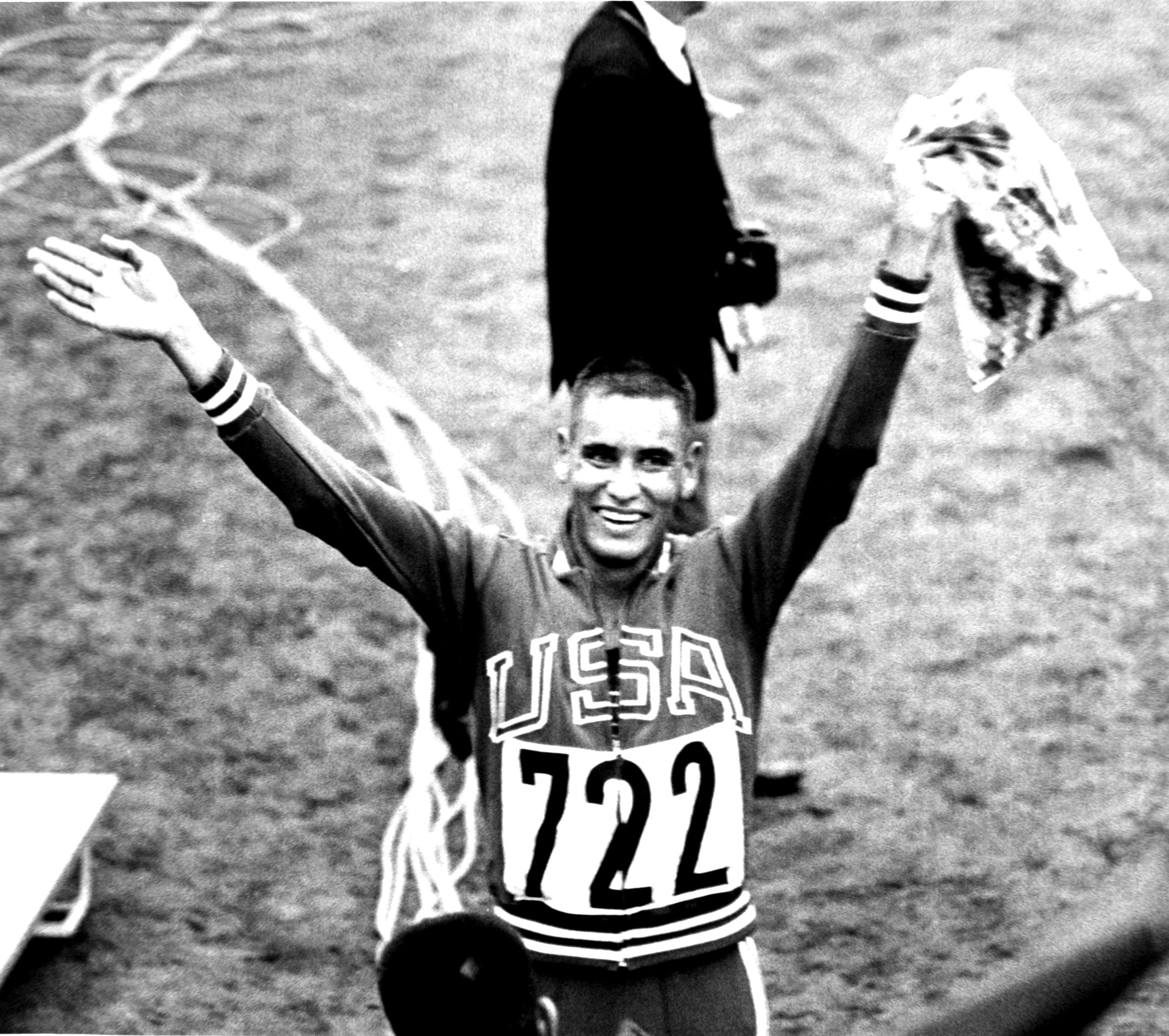

One lap to go. It’s a three man race: Ron Clarke of Australia and Mohammed Gammoudi of Tunisia lead. Fast on their trail is Billy. On the final turn before the finish, Clarke and Gammoudi are still out front. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, as they run down the homestretch toward Olympic glory, Billy took the lead.

“You can hear people screaming, but it’s quiet,” Billy recalls. “You can see reactions if you looked in the crowd, but it’s slow motion.”

“The tape breaks across my chest,” Billy says. ” ‘I won. I won. I won.’ An official came up and said, ‘Who are you?’ And I said, ‘Oh, my God, did I miscount the laps?’ He said, ‘Finished. Finished. You’re the new Olympic champion.’ “

Shortly after finishing, Billy reunited in the stadium with his wife, Pat. The two embraced.

” ‘Pat, I healed a broken soul,’ ” Billy remembers saying. ” ‘I healed a broken soul.’ And in the process, I became an Olympic gold medalist.”

Billy found himself suddenly famous.

“First telegram I read was from Col. John Glenn challenging me to a race,” Billy says. “He was a lieutenant in the Marine Corps as a pilot. And he said if he can’t beat me in his motorcycle, he reserves the right, since he outranks me, to use his spacecraft.”

The eyes of the world were on Billy, but he had been feeling uneasy even during the medal ceremony.

“The national anthem is being played,” Billy remembers. “It was beautiful. It was powerful. There’s total love for our country — our country I was willing to give my life for as an officer in the United States Marine Corps. But I also felt part of me did not belong. And I struggled with that.”

Billy dedicated the rest of his life to empowering American Indians. He wrote two books about Lakota life lessons with celebrated author Nicholas Sparks.

In 1986, he co-founded a nonprofit: Running Strong for American Indian Youth. They fund and run a diverse set of programs — from starting organic gardens on reservations to building community centers for kids to hosting holiday meals. They also tackle big, complicated projects to improve living conditions.

“It’s just an incredible opportunity to address infrastructure within the reservations — places where water has to be trucked, today, twice a week, for drinking, bathing, et cetera,” Billy says. “Here in America, third-world conditions.”

Throughout his life, Billy has received many accolades, including the NCAA’s top honor. He’s had a middle school in Kansas named after him. In 2013, President Barack Obama awarded Billy the Presidential Citizens Medal, the nation’s second highest civilian honor, for his work with Running Strong.

But Billy points to another honor as perhaps the most meaningful.

“When the Anti-Defamation League gave me the highest award they give to address hate, addressing, taking a stand against hate on a global basis — that’s been my life from the day I won the gold medal,” Billy says.

Today, Billy Mills, age 81, lives in Sacramento with Pat. They’ve been married 58 years. They raised four daughters who now have their own families.

When the summer Olympics head back to Tokyo for the first time since 1964, Billy plans to bring the family, plus one: a 14-foot bronze made by an American Indian sculptor that they hope will be displayed in Tokyo during the Games.

The statue shows Billy charging down the home stretch, arms pumping and knees driving on that October night 55 years ago that changed his life.

In interviews, Billy Mills was always known for acknowledging how fast his competition was. Reporters were quick to say, “Yes, but you’re faster.” Mills would fire back, “Yeah, but we’re not talking about me.” When he retired from competition, he began a successful career as a motivational speaker. A constant theme in his seminars that we should all learn from is to never let competition turn you into somebody you’re not.

Mills preaches, “As athletes and humans, yes, we are all competitive… on the track and in life. But competition can turn good people into villains. I was always trying to better my time from the previous race. If I ended up winning, that’s great… but if you’re in it just for the joy of beating people, then I don’t want to know you.”

In the Jewish faith tradition, hillul hashem, “profaning the name,” is an extremely dangerous sin. The rabbis found this in the way they interpreted the third commandment, “You shall not take the name of the Lord your God in vain, for the Lord will not leave him unpunished who takes His name in vain” (Exodus 20:7 NASB). Christians have traditionally interpreted this commandment has a prohibition against swearing, cursing. But of all ten commandments, this is the only commandment that God promises to punish. Why so serious?

In Jewish thought, this commandment is understood to have much greater meaning. The text literally says, “You shall not lift the name (reputation) of the Lord for an empty thing.” One of the ways that the rabbis interpreted this was as doing something evil publicly and then associating God with it. It is a sin against God himself, who suffers from having his reputation defamed (see “competition can turn good people into villains).

Consider the actions of the American pastor who burned the Qur’an on September 11, 2010. He intended to denounce Islam as falsehood, but instead it caused the Islamic community to see Christians as godless blasphemers who didn’t believe what Jesus taught about loving your enemies.

Outside of the public eye, in the lives of average people, you and I can be guilty of hillul hashem. Each of us is capable of defaming the name and reputation of God. And it usually starts with choosing to put ourselves first.

Think very seriously about this: In what way(s) do see Jesus followers committing hillul hashem? In what ways do you take God’s name in vain?

______________

Journal your thoughts. We will discuss this later in the month in the Circle…