All U.S. grocery stores at the beginning of the 20th century were full-service: You walked in with a list of items you needed, and then the grocer would gather those items. They’d weigh the flour or corn meal or butter or tomatoes, wrap everything up for you, and then charge it to your account. You’d either wait for the clerk to finish your shopping, or for a small fee, have your order delivered to your house later in the day. Like almost all grocery stores at the time, grocery stores also allowed customers to purchase food on credit, which the customer would then, usually, pay back over time.

Much like full-service gas stations, full service grocery stores began to close, thanks in part to the self-service grocery store revolution launched by one Clarence Saunders. Saunders was the self-educated child of impoverished sharecroppers. He eventually found his way to the grocery business in Memphis, Tennessee. He was 35 when he developed the concept for a grocery store that would have no clerks or counters but instead a labyrinth of aisles that customers would walk themselves, choosing their own food and placing it in their own shopping baskets.

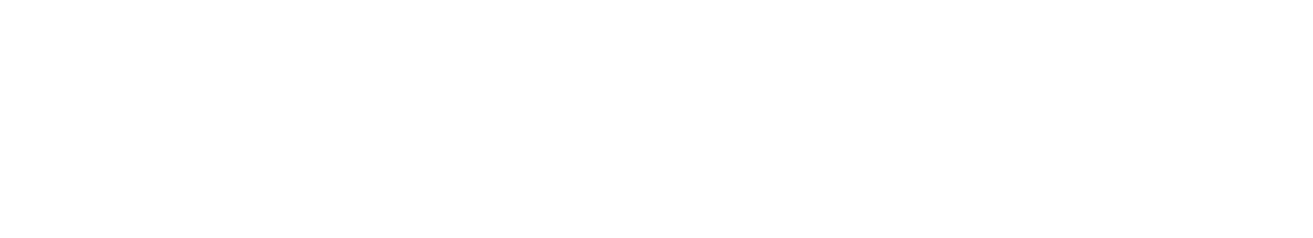

Prices at Saunders’ self-service grocery would be lower, because his stores would employ fewer clerks and also because he would not offer customers credit but instead expect immediate payment. The prices would also be clear and transparent — for the first time, every item in a grocery store would be marked with a price so customers would no longer fear being shortchanged by unscrupulous grocers. Saunders called his grocery store Piggly Wiggly.

Why? Nobody knows. When asked where the name came from, Saunders once answered that it arrived “from out of chaos and in direct contact with an individual’s mind,” which gives you a sense of the kind of guy he was. But usually when he was asked why anyone would call a grocery store Piggly Wiggly, he would answer, “So people will ask that very question.”

The first Piggly Wiggly opened in Memphis in 1916. It was so successful that the second Piggly Wiggly opened three weeks later. Two months after that, another opened — Saunders insisted on calling it Piggly Wiggly The Third to lend his stores the “royal dignity they are due.” He soon began attaching a catchphrase to his storefront signs: “Piggly Wiggly: All Around the World.” Of course, at the time, the stores were barely all around Memphis, but Saunders’ business did grow phenomenally quickly: Within a year, there were 353 Piggly Wiggly’s around the United States.

In newspaper advertisements, Saunders wrote of his self-service concept in nearly messianic terms. “One day Memphis shall be proud of Piggly Wiggly,” one ad read. “And it shall be said by all men that the Piggly Wigglys shall multiply and replenish the Earth with more and cleaner things to eat.” Another time he wrote, “The mighty pulse of the throbbing today makes new things out of old and new things where was nothing before.” Basically, Saunders spoke of Piggly Wiggly as today’s Silicon Valley executives talk of their companies — we’re not just making money here. We are replenishing the Earth.

Piggly Wiggly and the self-service grocery stores that followed did lower prices, which meant there was more to eat. They also changed the kinds of foods that were readily available—to save costs and limit spoilage, Piggly Wiggly stocked less fresh produce than traditional grocery stores. Prepackaged, processed foods became more popular and less expensive, which altered American diets.

Today, food prices are lower relative to average wage than they’ve ever been in the United States, but our diets are often poor — the average American ingests more sugar and sodium than they should, largely because of processed, prepackaged foods.

Brand recognition also became extremely important, because food companies had to appeal directly to shoppers, which led to the growth of consumer-oriented food advertising on radio and in newspapers, a phenomenon that Saunders understood better than almost anyone — during late 19s and early 20s, Piggly Wiggly was the single largest newspaper advertiser in the United States.

Of course, lower prices and fewer clerks also meant many people losing their jobs, including my great-grandfather. There’s nothing new about our fear that automation and increased efficiency will deprive humans of work. In one newspaper advertisement, Saunders imagined a woman torn between her long-time relationship with her friendly grocer and the low, low prices of Piggly Wiggly.

The story concluded with Saunders appealing to a tradition even older than the full-service grocer, with his protagonist saying, “Now away back many years, there had been a Dutch grandmother of mine who had been thrifty. The spirit of that old grandmother asserted itself just then within me and said, ‘Business is business and charity and alms are another.’” Whereupon our shopper saw the light and converted to Piggly Wiggly.

By 1922, there were over 1,000 Piggly Wiggly stores around the U.S. and shares in the company were listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Saunders was building a 36,000 square foot mansion in Memphis and had endowed the school now known as Rhodes College. But the good times would not last: After a few Piggly Wiggly stores in the northeast failed, investors began shorting the stock—betting that its price would fall. Saunders responded by trying to buy up all the available shares of Piggly Wiggly using borrowed money, but the gambit failed spectacularly, and Saunders lost control of Piggly Wiggly and went bankrupt.

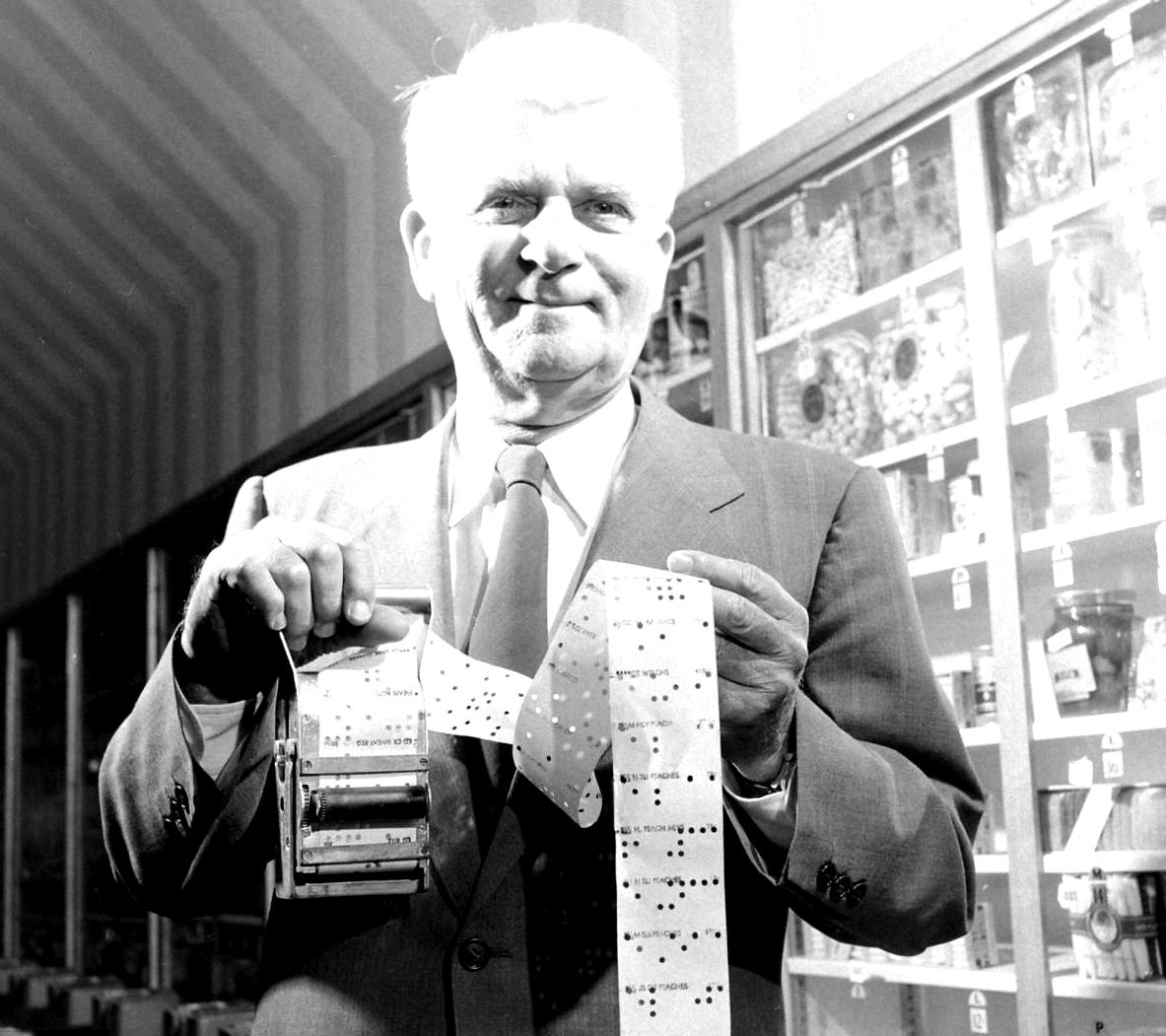

His vitriol at Wall Street short-sellers presaged contemporary corporate titans just as his reliance on big advertising and hyper-efficiency did. Saunders was by many accounts a bully—verbally abusive, cruel, and profoundly convinced of his own genius. After losing control of the company, he wrote, “They have it all, everything I built, the greatest stores of their kind in the world, but they didn’t get the man that was father to the idea. They have the body of Piggly Wiggly but they didn’t get the soul.” Saunders quickly developed a new concept for a grocery store—this one would have aisles and self-service but also clerks in the meat department and the bakery — basically, a contemporary supermarket. In under a year, he was ready to open, but the new owners of Piggly Wiggly took him to court, arguing that the use of the Clarence Saunders name in relation to a new grocery store would violate Piggly Wiggly’s trademarks and patents.

In response, Saunders defiantly named his new grocery store The Clarence Saunders Sole Owner of My Name Store, perhaps the only business name worse than Piggly Wiggly. And yet, it succeeded tremendously, and Saunders made a second fortune as Sole Owner stores spread throughout the South.

He went on to invest in a professional football team in Memphis, which he named The Clarence Saunders Sole Owner of My Name Tigers. Really. They played the Green Bay Packers and the Chicago Bears in front of huge crowds in Memphis and they were invited to join the NFL, but Saunders declined. Because he didn’t want to share revenue, or send his team to away games. He promised to build a stadium for the Tigers that would seat over 30,000 people. “The stadium,” he wrote, “will have skull and crossbones for my enemies who I have slain.”

But within a few years, the Sole Owner stores were crushed by the Depression, the football team was out of business, and he was broke again.

Meanwhile, the soulless body of Piggly Wiggly was faring quite well without Saunders — by the supermarket chain’s height in 1932, there were over 2,500 Piggly Wigglys in the United States. Even today, there are over 600, mostly in the South, although like many grocery stores, they are struggling under pressure from the likes of Wal-Mart and Dollar General, which can undercut traditional grocery stores on price partly by providing even less fresh food and fewer clerks than today’s Piggly Wiggly’s do. These days, Piggly Wiggly ads tend to focus on tradition, and the human touch. One North Alabama Piggly Wiggly TV spot from 1999 included this line, “At Piggly Wiggly, it’s all about friends serving friends,” a call to the kind of human-to-human relationships that Saunders ridiculed in that Dutch grandmother ad. The mighty pulse of the throbbing today does make new things out of old — but it also makes old things out of new.

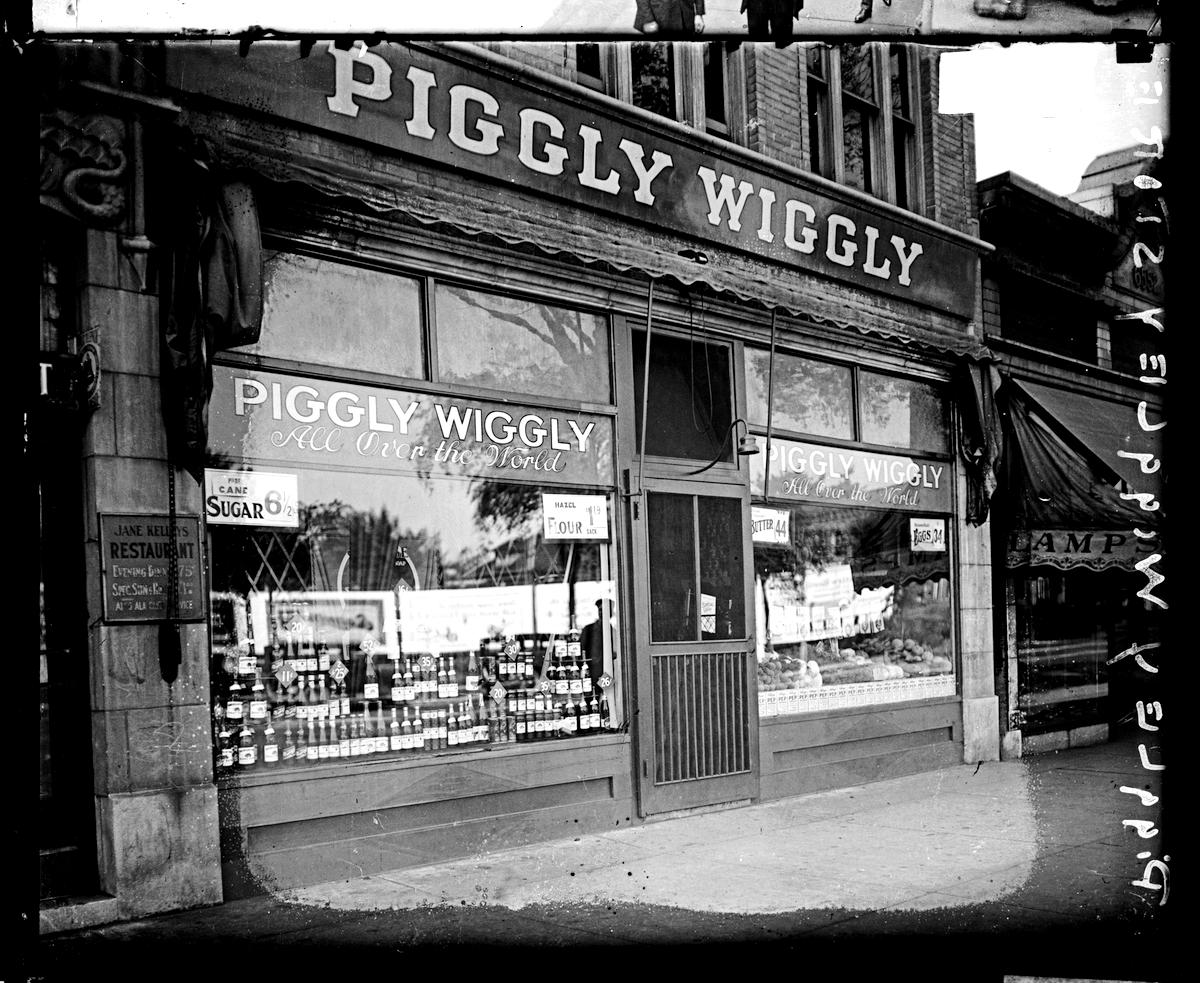

As for Clarence Saunders, he spent decades after his second bankruptcy trying to launch a new concept called the Keedoozle, a totally automated store that looked like a massive bank of vending machines and involved purchasing food with almost no human-to-human interaction. He was also one of the first business people to spend private money on newspaper advertising for political candidates — running ads, including virulently racist ones, for his preferred gubernatorial candidates.

Saunders grew more vitriolic and unpredictable as he aged. He could never get the Keedoozle to work—the machinery broke down constantly, and people found the shopping experience slow and clunky. He eventually entered a sanitarium that treated people with anxiety and depression. The mansion Saunders built with his first fortune became the Pink Palace Museum, Memphis’s science and history museum. The estate he built with his second fortune became Lichterman Nature Center. In 1936, the journalist Ernie Pyle said, “If Saunders lives long enough, Memphis will become the most beautiful city in the world just with the things Saunders built and lost.”

But Saunders never made a third fortune. He died at the Wallace Sanitarium in 1953, at the age of 72. One obituary opined, “Some men achieve lasting fame through success, others achieve it through failure.” Saunders was a huckster. He committed securities fraud. He helped usher in an era of food that fills without nourishing. He was also a genius ahead of his time who understood the power of branding and efficiency. But mostly, when I think of Piggly Wiggly, I think of it swallowing up the small-town grocery stores only to be swallowed itself by the likes of Wal-Mart, which will in turn be swallowed by the likes of Amazon. Joyce called Ireland the sow that eats her farrow, but Ireland has nothing on American capitalism.

(An excerpt from The Anthropocene Reviewed by John Green)

Theology — our study and beliefs about God — should be a natural process involving change instead of avoiding it. God is too big and too wonderful to completely understand by the time we graduate high school, or college, or reach a certain age.

Our life experiences, relationships, education, exposure to different cultures and perspectives continually affect the way we look at God. Our faith is a journey, a Pilgrim’s Progress, and our theology will change. And while we may not agree with a person’s new theological belief, we need to stop viewing theological change as something inherently negative.

In many ways, Jesus’s entire ministry was about changing the way people thought about God — changing their beliefs. Jesus was also lovingly patient with his disciples as they bumbled their way through mistake after mistake, and we need to be equally loving and gracious.

Interestingly, the people in the Bible who were the most self-confident about their beliefs were usually the ones who were wrong and rebuked by Jesus, while those who were humble and eager to learn were the ones Jesus used in powerful ways. Wise people admit when they’re wrong, but when it comes to theology most people spend all of their time and energy buttressing and protecting their own personal beliefs instead of critically, prayerfully, humbly, and honestly questioning them.

Are you spiritually arrogant or humble? Do you know what you don’t know?

Journal your thoughts. We will discuss this later in the month in the Circle…