It occurs to me that the phrase “in the meantime” seems a pretty good one for this moment. We really are living in the meantime. And here in that time, I have found comfort in a song.

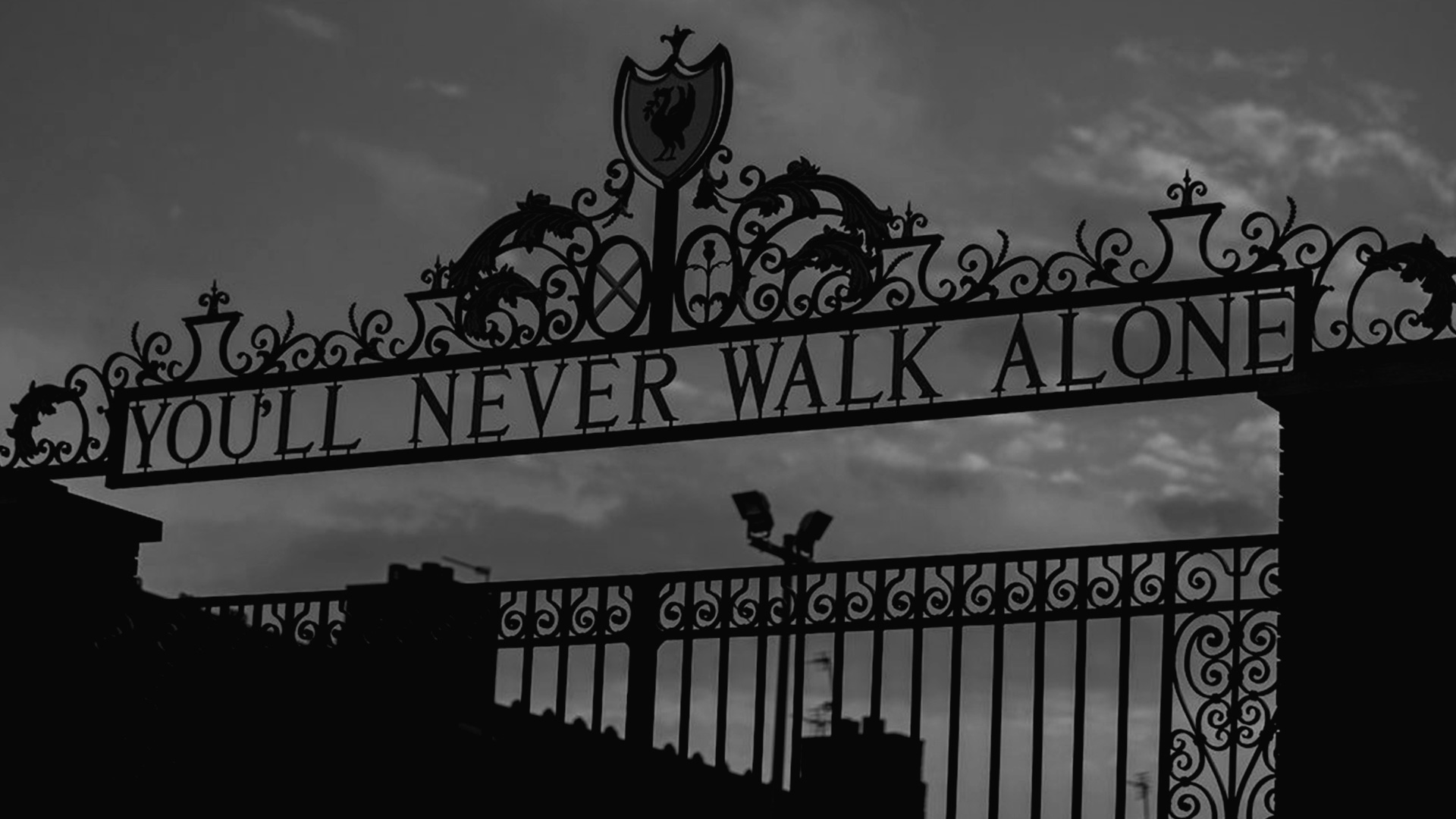

It started in Budapest in 1909, when the Hungarian writer Ferenc Molnar debuted his new play, Liliom. In the play, Liliom, a troubled and periodically violent young carousel barker, falls in love with a woman named Julie. And when Julie becomes pregnant, Liliom attempts a robbery to provide financial support for his burgeoning family, but the robbery is a disaster, and Liliom dies. He ends up in purgatory and then sixteen years later, he is allowed a single day to visit his now-teenage daughter, Louise.

The play flopped in Budapest, but Molnar was not a playwright who suffered from a shortage of self-belief, so he continued trying to stage productions around Europe and then eventually in the U.S., where a 1921 translation of the play attracted good reviews and moderate box office success.

The story might have ended there if it hadn’t been for Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein. The composer Giacomo Puccini wanted to adapt Liliom into an opera, but Molnar refused to sell him the rights saying, “I want Liliom to be remembered as a play by Molnar, not as an opera by Puccini.” Instead, Molnar sold the rights to Rodgers and Hammerstein, the musical theater duo who were fresh off the success of Oklahoma with An Exclamation Point, and who reworked Liliom into the only version of it now remembered, the famed musical Carousel, which debuted in 1945.

In the musical, Rodgers and Hammersteins’ song “You’ll Never Walk Alone” is sung twice — first to encourage the newly widowed Julie after her husband’s death, and then by Louise’s classmates years later, at a graduation ceremony. Louise doesn’t want to join in the song–she’s too upset–but even though her father is now invisible to her, Louise can feel his presence and encouragement, and so eventually she starts to sing.

The lyrics of “You’ll Never Walk Alone” contain only the most obvious metaphors: It tells us to walk on through the wind and through the rain, which are among the most common obstacles one might face when walking. It tells us to walk on with hope in our hearts, which is just aggressively cheesy. And yet, it works. Maybe it’s the song’s repetition of those words, “Walk on.” I mean, I think two of the fundamental facts of being a person are (1) Whether we can walk or not, we must go on. And then also (2) None of us ever walks alone. We may feel alone — in fact, we will feel alone — but even in the crushing grind of isolation, we aren’t alone. Like Louise at her graduation, those who are distant or even gone are still with us, still encouraging us to walk on.

The song has been covered by, like, everyone — from Frank Sinatra to Johnny Cash to Aretha Franklin. In 2020, a version of the song partly sung by a 99-year-old World War II veteran shot to the top of the charts in the UK, where “You’ll Never Walk Alone” has become a kind of anthem for this moment. But the most famous cover of the song came in 1963 from Gerry and the Pacemakers, a band that like the Beatles, were from Liverpool, managed by Brian Epstein, and recorded by George Martin. In keeping with their band name, the Pacemakers changed the meter of the song, increasing the tempo, giving the dirge a bit of pep to it, and their version, sung by Gerry Mardsen, was a #1 hit in 1963. And fans of Liverpool Football Club almost immediately began to sing the song together in the stands during games.

That summer, when Liverpool’s legendary manager Bill Shankly heard Gerry and the Pacemakers play “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” Shankly famously told Gerry Mardsen, “Gerry, my son, I have given you a football team, and you have given us a song.”

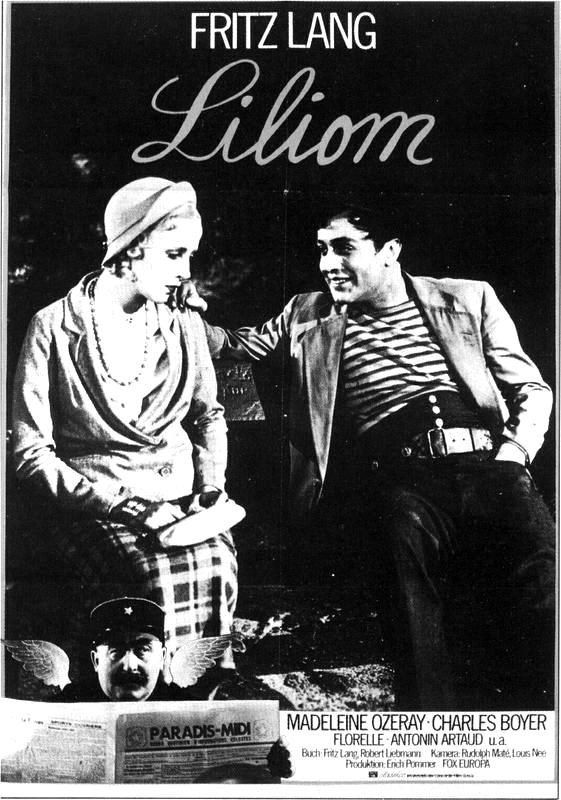

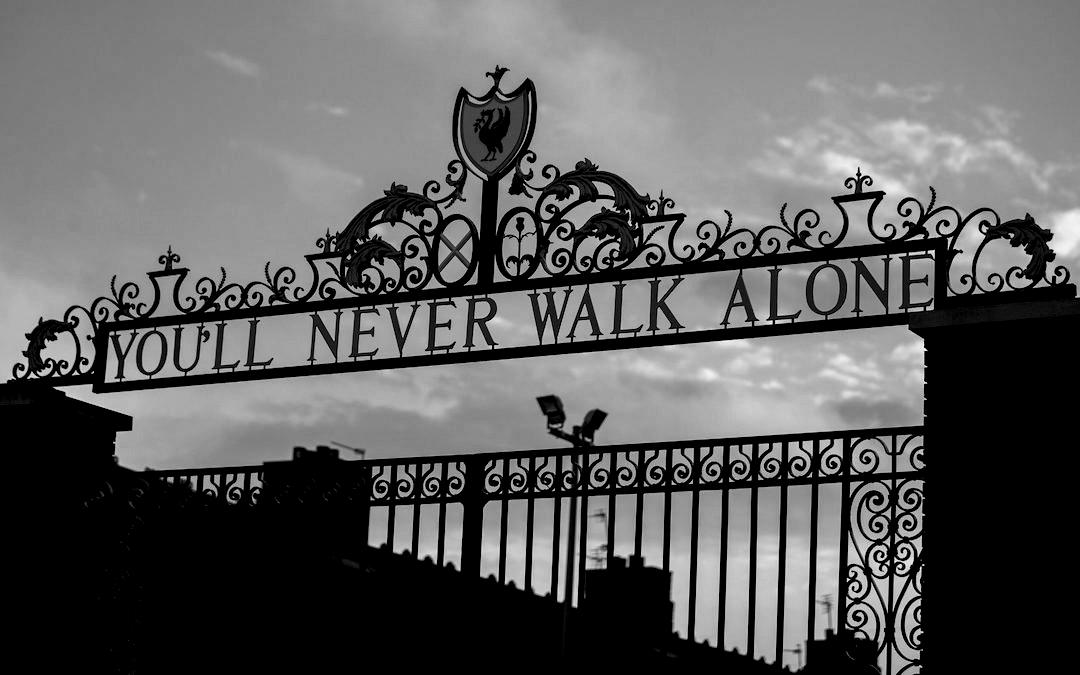

Today, the words “You’ll Never Walk Alone” are etched in wrought iron above the gates of Anfield, Liverpool’s stadium. Liverpool’s famous Danish defender Daniel Agger has YNWA tattooed on the knuckles of his right hand. Whenever Liverpool fans gather, the song is sung at the beginning and end of every game — sometimes in exaltation, often in lamentation. When Bill Shankly died in 1981, Gerry Mardsen sang “You’ll Never Walk Alone” at the memorial service — as it has been sung at many funerals for many Liverpool supporters.

And part of the genius of the Pacemakers’ version of “You’ll Never Walk Alone” is its adaptability; former Liverpool player and manager Kenny Dalglish said, “It covers adversity and sadness and it covers … success.” It’s a song about sticking together even when your dreams are “tossed and blown.” It’s a song both about the storm and about the golden sky that dawns afterward.

At first blush, it may seem odd that the world’s most popular football song comes from musical theater, since “theater people” are often imagined in opposition to “jocks” or sporty types. But football is theater, and fans make it musical theater. The anthem of West Ham United is called “I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles,” and at the start of each game, you’ll see thousands of grown adults blowing bubbles from the stands as they sing, “I’m forever blowing bubbles, pretty bubbles in the air, They fly so high, nearly reach the sky, then like my dreams they fade and die.”

Manchester United fans refashioned Julia Ward Howe’s U.S. Civil War anthem “Battle Hymn of the Republic” into the song “Glory, Glory Man United.” Manchester City fans sing “Blue Moon,” a 1934 Rodgers and Hart number. All these songs are made great by the communities singing them–they are celebrations of unity and togetherness–in sorrow and triumph, through the wind and through the rain. When the bubble is flying, and when the bubble is popping.

I know the lyrics are cheesy, but the thing about “You’ll Never Walk Alone” is that the lyrics aren’t wrong.

Like, they don’t claim the world is a just or happy place. They don’t minimize suffering or fear. But still, we find ways to walk on with hope in our hearts. And just like Louise at the end of Carousel, even if you don’t really believe when you start singing that you’ll never walk alone, you believe it a little more when you finish. And because the song is addressed to “You,” in singing it, you are preaching this good news not just to yourself, but to everyone who can hear you.

A couple weeks ago a video made the rounds online in which a group of UK paramedics sang through a glass wall to their colleagues on the other side, who were working in an Intensive Care Unit.

You’ll never walk alone.

The stadia are empty. But even now, especially now, we must find ways to sing to each other, and to encourage each other. What a word that is, encourage. Though our dreams be tossed and blown, still, we sing ourselves and one another into courage, and we walk on.

(An excerpt from The Anthropocene Reviewed by John Green)

The connectivity of the body of Christ is foreign to so many of us. Scripture tells us that we are all individual parts of one body. Paul elaborates and puts it this way:

The body is a unit, though it is made up of many parts; and though all its parts are many, they form one body. So it is with Christ… Now the body is not made up of one part but of many. If the foot should say, “Because I am not a hand, I do not belong to the body,” it would not for that reason cease to be a part of the body. And if the ear should say, “Because I am an eye, I do not belong to the body,” it would not for that reason cease to be a part of the body. If the whole body were an eye, where would the sense of hearing be? If the whole body were an ear, where would the sense of smell be?

Paul says that, as Jesus followers, we are all one “unit” but made up of many “parts.” A Jesus follower can’t decide that, because they don’t desire to be connected, he or she doesn’t belong to the body. When you start following Jesus, you become a part of the body of Christ. Furthermore, Paul says that if I am an eye, without an ear, how can I hear? If I am an ear, without a nose, how can I smell?

If you want to see how the body of Christ was intended to work, just go stump your big toe on your bedpost. What will transpire is a living example of how God intended us, the parts of the body of Christ, to respond to one another:

- Nerves send a signal to your brain that you are in pain in the South Pole region…

- Your brain sends a signal everywhere…

- Your hands respond by grabbing your toe…

- Your mouth responds by screaming (what you scream optional)…

- Your eyes respond by tearing up…

- Your good leg responds by jumping up and down…

All of this happens in a matter of seconds! The parts of the body respond to the part of the body that is injured.

Without the arm, the hand can’t function. Without the brain, the hand can’t function. Without the heart, the hand can’t function. The implication is clear: without the rest of the body, that hand, at the very least, would never exist for its purpose or, at worst, would be rendered useless.

Are you like a hand that decides it does not need input or any help from the rest of the body? If so, you are risking a life of spiritual impotence and zero influence. Why do you need accountability at this point of your journey?

__________

Journal your thoughts. We will discuss this later in the month in the Circle…