A seder is the ritual feast that marks the beginning of the Jewish holiday of Passover. A beautiful celebration through storytelling and prayers, it allows Jewish brothers and sisters to recall and reflect on the ways God intervened to deliver the Hebrews from slavery.

When reading the prayers from the Haggadah — the text that contains the seder order of service, prayers, songs and questions — one moment stands out. During the recitation of the ten plagues (see below), parishioners spill ten drops of wine with a reminder to never gloat over the death of an enemy.

“They are made in the image of God just like us.”

These are the Ten Plagues which the Holy One, blessed be He, brought upon the Egyptians, namely as follows:

When saying the ten plagues, spill from the cup itself ten times, as stated above (and when spilling, again have in mind what was said above). The wine remaining in the cup (will have become ‘wine that causes joy,’ thus) is not to be spilled, but other wine is added to it [to refill the cup].

Blood.

Frogs.

Lice.

Wild Beasts.

Pestilence.

Boils.

Hail.

Locust.

Darkness.

Slaying of the First-born.

Perhaps this prayer should rattle and convict us. Perhaps we should take the story to its logical conclusion. All of the Egyptians experienced extreme suffering. Of all of the times you place yourself in the shoes of Moses, has your moral imagination ever called you to think about the Egyptian parents who lost a son or the soldiers who died because they were following Pharaoh’s orders?

So Moses said, “This is what the Lord says: ‘About midnight I will go throughout Egypt.Every firstborn son in Egypt will die, from the firstborn son of Pharaoh, who sits on the throne, to the firstborn son of the female slave, who is at her hand mill, and all the firstborn of the cattle as well. (Exodus 11:4-5)

Then the Lord said to Moses, “Stretch out your hand over the sea so that the waters may flow back over the Egyptians and their chariots and horsemen.”Moses stretched out his hand over the sea, and at daybreak the sea went back to its place. The Egyptians were fleeing toward it, and the Lord swept them into the sea.The water flowed back and covered the chariots and horsemen—the entire army of Pharaoh that had followed the Israelites into the sea. Not one of them survived. (Exodus 14:26-28)

Evil perpetrators and innocent victims make for memorable moral lessons, but our world is rarely so neat. Each of us is capable of good and evil, spirited activism and cold indifference.

The history of group conflict would support the hypothesis that there were surely Egyptians who opposed Pharaoh’s policies toward the Hebrews. Many Egyptians may have fought for abolition alongside Moses and the Hebrews.

Did these Egyptians suffer the loss of their firstborn son too?

Unfortunately the history of the United States bears witness to the ways the choices of a few can have an incredible impact on so many. Injustice and evil anywhere can cause pain and suffering everywhere.

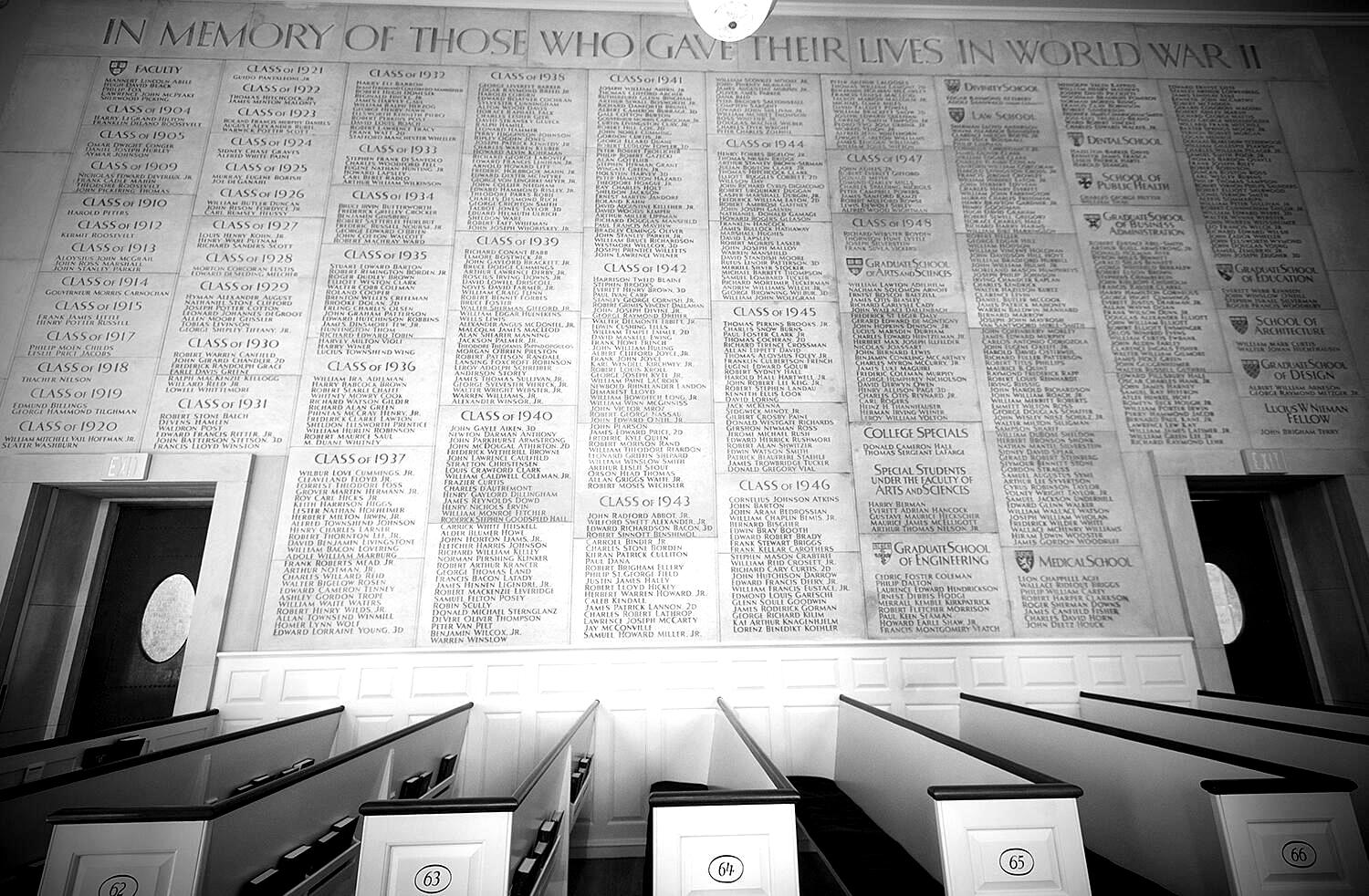

The 1,113 names of the war dead engraves on the walls of the Memorial Church at Harvard University — men and women who lost their lives in World War I, World War II, Korea and Vietnam — remind me of how choices made by people in one place can cause tragedy for families continents away.

There is one particular name on the wall that should catch your eye if you ever visit the hallowed halls of Memorial Church.

The name is Adolf Sannwald.

And under his name, in parenthesis, reads these words: Enemy Casualty.

Adolf Sannwald studied at Harvard Divinity School during the 1924‑1925 academic year. He was killed in World War II on the side of the Germans. That’s why, under his name, you will see in parentheses Enemy Casualty.

Further research on Sannwald, however, revealed that he was much more of a complicated figure than originally thought.

Far from being a Nazi, far from being a part of the Third Reich, this Lutheran pastor, Adolf Sannwald, was a part of the Confessing Church Movement, an underground Christian resistance movement that opposed Adolf Hitler and was led by their great martyr, Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

In 1934, Sannwald published a pamphlet that repudiated Nazism’s view of racial supremacy. “God did not choose his children on the basis of race,” Sannwald argued. “We can not and will not confuse faith in Jesus Christ with some other faith in a religious or political world view.”

As the pastor of St. Mark’s Church in Stuttgart, Sannwald spoke out loud and crystal clear against Nazism’s view of racial supremacy. Their church offered shelter to fugitive Jews who were trying to flee.

The German Army drafted Sannwald in 1942. Due to his sermons that were critical of the Third Reich regime, he was not allowed to serve as a chaplain in the German Army. Germany designated him a “common soldier” and sent him to the frontlines in Russia. Within a year of being drafted, Adolf Sannwald was killed in a Russian bombing air raid.

Sunnwald did have one opportunity to preach as a member of the German Army. It was on Easter Sunday, 1943. His topic? The resurrection and collective guilt.

Sannwald’s life and death is a tragic lesson about how the dividing line between innocence and guilt can often be too thin to attribute heroism or blame. Moreover, suffering is no respecter of person. The storms of injustice rain on the guilty and innocent alike. So whether they were Hebrew or Egyptian, all paid a terrible price for the sin of viewing one group of people as superior to another. This is why individual Egyptian claims of “I did not enslave anyone” or “I am not guilty” were irrelevant when the death angel showed up. Categories of good and evil, guilty and innocent, miss the point when we are working on behalf of social justice. This language is too individualized and interpersonal. It allows us to evade responsibility and ignore our culpability.

A better way of thinking about injustice involves whether or not we are wiling to take responsibility for one another. Are we our brothers’ and sisters’ keepers? The writer James Baldwin put it eloquently: “I’m not interested in anybody’s guilt. Guilt is a luxury that we can no longer afford. I know you didn’t do it, and I didn’t do it either, but I am responsible for it because I am a man and a citizen of this country and you are responsible for it, too, for the very same reason.”

May we imagine a world where we realize we are all responsible for injustice.

If not, we may just find ourselves mourning one another at the Red Sea.

(Inspired by an excerpt from A Lens Of Love by Jonathan L. Walton)

Let’s consider the plagues that the book of Exodus records that God unleashed on Egypt: Blood. Frogs. Lice. Wild Beasts. Pestilence. Boils. Hail. Locust. Darkness. Slaying of the First-born. An elementary reading of these plagues can make each plague seem kind of random. However, a more informed understanding shows that the plagues are full of symbolic meaning.

The Egyptians considered Pharaoh to be a god, the Nile River was sacred, and the Egyptian goddess of fertility Hequet had a frog’s head. Therefore, the exodus narrative makes a demonstrative theological claim when Yahweh turns the Nile into blood, unleashes frogs throughout the nation, and turns the sun black. The God of the Hebrews is more than just caring and compassionate: He is stronger than all of the gods of Egypt. And the end of the exodus story drives home another point as well: by creating a highway through the Red Sea, Yahweh is a powerful deliverer.

The exodus is a theological account of an all-powerful God who can save and deliver.

But have you ever given much thought to any other character in this story other than Moses and Yahweh? What about Egyptian mothers and soldiers? Like Adolf Sannwald, could they be more than just an enemy casualty?

So let’s consider two things:

The first is this: in the words of Zora Neale Hurston, “If you want that good feeling from doing the right thing from other people, sometimes you have to pay for it with abuse and misunderstanding.” As a next generation leader, are you prepared for abuse and misunderstanding?

The second thing we want you to consider is that if you are a truth‑teller, when you speak up and speak truth to power and disrupt the status quo, when you give voice to the voiceless, when you give visibility to those who have been rendered invisible, when you actually breathe life of truth into the dry bones of quotidian facts, you might end up being called an enemy casualty or enemy of the people. As a next generation leader, are you OK with being an enemy casualty?

Remember the words of James Russell Lowell, “Truth forever on the scaffold, wrong forever on the throne. Yet that scaffold sways the future, standeth God within the shadows keeping watch above His own.”

__________

Journal your thoughts. We will discuss this later in the month in the Circle…