One of the most visited landmarks in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, “The City of Brotherly Love,” is the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The seventy-two stone steps that lead to the entrance of the Philadelphia Museum of Art have become known as the “Rocky Steps” as a result of a scene from the film Rocky. Only a few dozen feet from the base of those steps stands a statue of a fictional boxer named Rocky Balboa, “The Italian Stallion.”

Can we stop for a second and ask ourselves: how does a statue of a fictional boxer and 72 stone steps become one of the most frequented landmarks in the cradle of our country’s existence?

The Rocky movie franchise has earned over $1.4 billion at the box office, making it one of the most successful franchises of all time. While most people have heard the story of Rocky Balboa (the washed up fighter who ends up fighting for the title) few know how it was made.

It is truly one of the most inspiring Hollywood stories of all time.

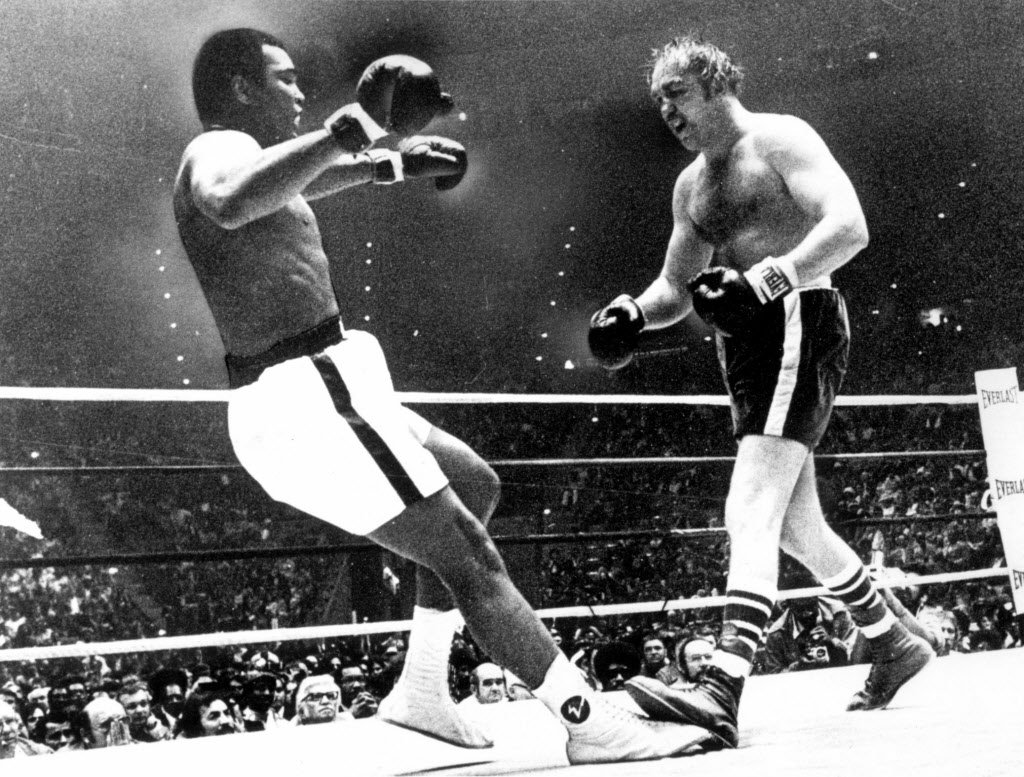

On March 25, 1975, heavyweight boxing legend Muhammed Ali fought a little-known fighter named Chuck Wepner in Cleveland, Ohio. Wepner, a big, loafing brawler, was nicknamed “The Bayon Bleeder,” not because of his prowess as a boxer, but rather because most of his fights ended with Wepner profusely bleeding. It was believed that, leading up to the fight, Ali did not take the fight with Wepner seriously, and the way the fight unfolded proved this theory true. Ali seemed listless and bored and allowed Wepner to stay in the fight. Then, in the 9th round, Wepner knocked down Ali (close examination of the footage shows that Wepner actually stepped on Ali’s foot and Ali tripped). Wepner immediately turned his back on Ali laying on the ground, walked to his corner and said to his manager, “Al, start the car. We’re going to the bank. We are going to be millionaires.” To which Wepner’s manager replied, “You better turn around. Ali is getting up and he’s really angry.” The next six rounds can only be described as brutal. Ali pummeled Wepner. But somehow Wepner never went down and finished the fight. From that point on, Wepner could hold his head high forever no matter what happens: he went 15 rounds and established himself as one of the few men who had ever gone the distance with Muhammad Ali.

That same night in 1975, 2,300 miles away, sitting in a movie theater in Los Angeles watching the fight, was a struggling sometime actor-turned-screenwriter named Sylvester Stallone. He had $106 in the bank. His wife was pregnant and he couldn’t pay the rent on his seedy Hollywood apartment. Stallone had just moved to Los Angeles from New York City. ”I was watching the fight in a movie theater,” Stallone said, ”and I said to myself, ‘This is a story about stifled ambition and broken dreams and people who sit on the curb looking at their dreams go down the drain.’” Stallone wrote the Rocky script in three and a half days. He would get up at 6:00 am and write it by hand, with a Bic pen on lined notebook sheets of paper. Then his wife, Sasha, would type it. Stallone says that his wife kept saying, “You’ve gotta do it, you’ve gotta do it. Push it, Sly, go for broke.” Only 90 pages, and only about a third of it was used in the movie, but Stallone had his script.

It makes sense why Stallone would be inspired by Chuck Wepner. Stallone’s own life story might serve as material for a movie. Born to a bickering Italian couple in Hell’s Kitchen, Stallone was farmed out to foster homes while his parents worked. He grew up in Monkey Hollow, Maryland, where his mother ran a health spa. Stallone, considered a juvenile delinquent, attended 12 schools by the time he was 15 years old, and was kicked out of most of them. After high school in Philadelphia, where he had been a star fullback and discus thrower, Stallone enrolled at the American College in Leysin, Switzerland. Finding that money was scarce, he teamed up with a classmate to open a hamburger stand for students who had never tasted them before. Another part-time job requiring him to shoo men away from the girls’ dormitory helped earn his plane fare back to America. He flew to the University of Miami, where he studied drama for two years, then moved to New York City to become an actor. Instead, he found work cleaning the lions’ cages at the Central Park Zoo and ushering at the Baronet Theater, where he was fired for trying to scalp tickets.

Weeks after writing the Rocky script, Stallone was on a casting call for an acting role and quickly realized that he wasn’t right for the part. On the way out he told the producers about the story he was writing. They told them to bring it by later. He did. They read the script and loved it, except for one thing: They didn’t want to have Sylvester Stallone play the main character, Rocky. You can’t blame them. Stallone was an unknown actor at the time and other Hollywood types would be a much safer bet at the box office.

From the beginning, Stallone intended to play Rocky. Although there was much interest in Hollywood for his script, the money men all wanted a name actor in the part. The bidding for the script went up to $360,000 for the script, with the condition that he wouldn’t play Rocky. Remember that he had no car, $106 in the bank, and sold his dog to pay the bills (Stallone had to sell his bull mastiff named Butkus for $50 because he couldn’t afford to feed the dog and needed money). Stallone refused to sell unless he could play the lead.

By stubbornness and sheer luck, the producers eventually relented and gave Stallone $1,000,000 to make the movie, starring himself. Stallone promptly traveled across country by train and bought Butkus back for $15,000 once he sold the Rocky script to the studio (and Butkus would become a fixture in the Rocky franchise).

$1,000,000 was an extremely low budget for a film, even in the 1970s. The production crew came in under budget by using Stallone’s family and friends in the cast, handheld cameras, and only using one take to film most of the footage. With a handheld camera, Stallone would jump out of a van and start running at the docks, down the streets of Little Italy in Philadelphia, with fruit and meat stand vendors throwing things at him. It was less than glamorous, to say the least.

While exceptional seasoned actors Meredith Burgess, Burt Young, and Taia Shire were cast for important roles, finding an actor to play heavyweight champion Apollo Creed, Rocky’s opponent and nemesis, was a much more difficult task. After legendary boxers Ken Norton and Joe Frazier turn down the role of Apollo Creed, a former NFL football player named Carl Weathers came in to read for the part. Weathers exuded confidence, bordering on arrogance, telling producers how right he was for the part, and after reading the role of Apollo Creed opposite Stallone, turned to the producers and complained: “I would have done much, much better if you had given me a real actor to read with.” He insulted Sylvester Stallone during the reading… and was hired immediately to play the part of Apollo Creed.

While Weathers was an elite athlete, with a sculptured body perfect for a champion, Stallone was a 5-foot-10-inch, 175-pound actor who had never had any formal boxing instruction. Stallone went into training six hours a day for five months before Rocky began filming. Stallone got up at dawn to run five miles on the beach, shadow-boxed around the apartment, and worked out at a gym, where he punched the punching bag, did pushups, and had a medicine ball thrown into his stomach. He was preparing for the film’s climax, the championship fight, which he and director John Avildsen choreographed punch-for- punch. There were 14 pages of exact punch and counter-punch sequences, transcribed from Stallone using a tape recorder and acting as if he was a radio commentator calling the fight blow by blow.

What looked like haphazard throwing of punches was an exact ballet. Stallone felt that the film had to go 15 rounds nonstop. To do that meant the film crew and actors had to know exactly what they were doing every minute for 45 minutes of boxing: the time of a heavyweight fight, 45 minutes of boxing, 15 minutes of rest. Stunt men hired to rehearse each punch-by-punch sequence of the fight scenes with Stallone and Weathers quit, stating “it couldn’t be done… it would look stupid.” Stallone and Weathers rehearsed for more than 35 hours to choreograph the fight scenes. Nearly every day Weathers would fly down from Oakland and Stallone and he would work the equivalent of four to five hours a day. In the final analysis, the ring fight in the movie runs a little more than nine minutes. For all the hours in training, it broke down to thirty-five and a half hours of boxing rehearsal for each minute of fighting (as opposed to 1-2 hours rehearsing each round in most fight films). Stallone and Weathers watched every fight film from beginning to end and every authentic boxing movie made. The fight films went as far back as the early 1900s, the first being the Jack Johnson versus Stanley Ketchell match, and finally ending watching the great Muhammad Ali versus Joe Frazier “Thrilla in Manila” struggle of 1975.

When the Rocky film started being screened around Hollywood, it received a ton of positive reaction from the general public. The real test, however, was when it was screened at The Director’s Guild, in front of 900 movie industry men and women. The theater was packed, but the movie, according to Stallone, “was playing terrible.” Stallone said, “The laughs weren’t coming where they were supposed to. The fight scenes seemed to be listless, as the response was. And I just sat there, as everyone left the theatre, and I couldn’t believe it. I really blew it. I was humiliated and saddened by it.”

Stallone eventually left the theater, with his mother by his side, and they walked down three flights of stairs to exit out of the theatre. As they rounded the landing to the last flight of stairs, all 900 movie industry men and women who had screened the film were standing at the bottom of the stairs waiting for him. The foyer of the theatre erupted in applause.

The original Rocky film went on to receive nine Oscar nominations, winning three Academy Awards, including Best Picture, and grossed over $200 million.

Fast forward ten years later to a March 23, 1986. A baby boy was born in Oakland, California to Joselyn and Ira Coogler. They named their son Ryan. Ryan grew up playing basketball and football. His father Ira, a huge fan of the Rocky movies, would make Ryan watch Rocky 2 before every big football or basketball game he played in.

In 2011, 25 year-old Ryan Coogler was finishing film school at USC when his father, Ira, a probation officer, became stricken with a mysterious neurological illness that left him nearly unable to walk. Knowing how much his ailing dad loved the Rocky movies, Coogler began mulling over a way to bring back the series as a kind of father-son story, with Rocky serving as the mentor and paternal figure to Apollo Creed’s son. With no pull in Hollywood, Coogler, who had yet to shoot a single frame of what would become his debut feature, the drama Fruitvale Station, figured the idea would never get off the ground. Still, he started working on a script with his friend Aaron Covington and eventually scored a meeting with Stallone at the actor’s office.

Stallone, who had written all six films in the Rocky series and directed four of them, had a hard time wrapping his head around Coogler’s out-of-left-field pitch. That’s not to say Stallone couldn’t appreciate where Coogler was coming from. He had been a virtual unknown before being launched to worldwide fame as Rocky Balboa.

Then in 2013, Stallone saw Fruitvale Station, which starred Michael B. Jordan and premiered to critical acclaim at that year’s Sundance Film Festival, and began to reconsider Coogler’s idea. With some trepidation, Stallone agreed to sign on to Creed.

INFLUNSR defines grit as choosing passion over distraction. Grit is the result of one thousand invisible mornings, when everyone else is distracted, but you decide to invest in, to chase your passion.

Here are three questions we want you to consider today:

How does the story of the making of Rocky and Creed illustrate grit?

Why does grit matter as it relates to influence? In your mind, if grit is choosing passion over distraction, what are the components of that make up that choice? How does your student(s) mesh with these four ideas: interest, practice, purpose and hope.

How do you develop students that are gritty? How you build grit? How do you get your student(s) to the thing that they want to be doing? What is the path?