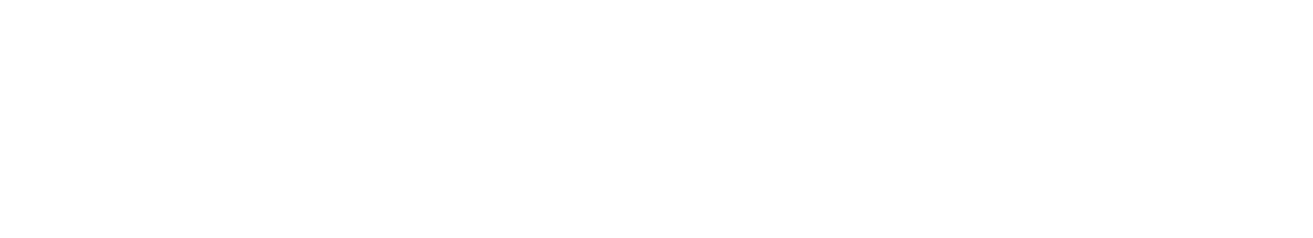

Learning Humility from Lincoln

Doris Kearns Goodwin’s book, Team of Rivals, depicts the governing team that Abraham Lincoln forged with many of his previous political rivals. On May 18, 1860, William H. Seward, Salmon P. Chase, Edward Bates, and Abraham Lincoln waited in their hometowns for the results from the Republican National Convention in Chicago. When Lincoln emerged as the victor, his rivals were dismayed and angry.

Throughout the turbulent 1850s, each had energetically sought the presidency as the conflict over slavery was leading inexorably to secession and civil war. That Lincoln succeeded, Goodwin demonstrates, was the result of a character that had been forged by experiences that raised him above his more privileged and accomplished rivals. He won because he possessed an extraordinary ability to put himself in the place of other men, to experience what they were feeling, to understand their motives and desires.

It was this capacity that enabled Lincoln as president to bring his disgruntled opponents together, create the most unusual cabinet in history, and marshal their talents to the task of preserving the Union and winning the war.

Goodwin shares two incidents from 1855 that reveal the exemplary character of the 16th President. By humbling himself and his ambitions, Lincoln modeled a generosity of spirit rarely seen in public life.

In the first event, Goodwin reports that in February of 1855, after several weeks delay due to severe snow storms, the Illinois Senate was seated to elect the next Senator. After the first ballot, Lincoln led with 45 votes (a majority of 51 was needed), James Shields received 41, and Congressman Lyman Trumbull held 5 votes.

Trumbull was aligned with the antislavery party and expected he would eventually have to yield his votes to Lincoln. After nine ballots, Lincoln held a high of 47 votes, but the five voters for Trumbull, led by Norman Judd of Chicago, refused to yield and give Lincoln the victory.

At this point Lincoln realized that the only way for the antislavery coalition to win was to yield his votes to Trumbull and allow Trumbull to be the next Senator from Illinois. According to Goodwin, Lincoln “advised his floor manager, Stephen Logan, to drop him for Trumbull. Logan refused at first, protesting the injustice of the candidate with the much larger vote giving in to the candidate with the smaller vote.”

Lincoln was adamant and said, “You will lose both Trumbull and myself and I think the cause in this case is to be preferred to men.”

Trumbull became the next Senator from Illinois and Lincoln “expressed no hard feelings toward either Trumbull or Judd. He deliberately showed up at Trumbull’s victory party, with a smile on his face and a warm handshake for the victor.”

As a young man attempting to forge his career, to step back without resentment and allow a colleague with 5 votes to prevail when he was holding a near decisive total displays a unique ability to put a higher good ahead of personal desires. The point of the vignette is not the outcome, but Lincoln’s bold decision.

Yet Goodwin reports a happy ending in that “Neither Trumbull nor Judd would ever forget Lincoln’s generous behavior. Indeed, both men would assist him in his bid for the U.S. Senate in 1858, and Judd would play a critical role in his run for the presidency in 1860.”

The other incident Goodwin chronicles was also in 1855 when Lincoln was retained to be co-counsel in a patent case McCormick vs. Manny. The attorney for Manny, George Harding, expected the case to be tried in Chicago and thought it would be advantageous to have local Illinois representation and was recommended to Lincoln.

Lincoln was very pleased to work on a high profile case and worked diligently to prepare. At the last minute, the case was moved to Cincinnati, Ohio. Lincoln did not receive instruction on how to proceed, so he traveled to Cincinnati to present the case with Harding.

After Lincoln arrived, he saw Harding walking in the street with one of the best patent attorneys of the day, Edwin Stanton. Lincoln introduced himself, and Stanton said to Harding:

“Why did you bring that… long armed ape here….he does not know anything and can do you no good.”

Stanton and Harding made it plain to Lincoln that he should withdraw from the case. Lincoln did withdraw but stayed to watch the trial.

Harding and Stanton were rude and insulting. But Lincoln was interested in the trial and stayed until its completion. He had every reason to be upset with these two men, yet Lincoln maintained his demeanor and did not alienate his fellow attorneys. They must have respected him because Stanton went on to become Lincoln’s Secretary of War when Lincoln became President.

What Lincoln displayed to his rivals in both this anecdotes was a startling ability to allow, even facilitate, the success of a rival.

It is easy to imagine that his adversaries might view this subordinating of his own ambitions as a weakness unworthy of a leader. But what they came to understand was that on display was not weakness of character but strength so indomitable that it could endure insult and defeat in order to accomplish his goal.

By humbling himself, Lincoln gained the respect of his rivals and challenged the conventional wisdom that to get ahead, you must leave your rivals behind.

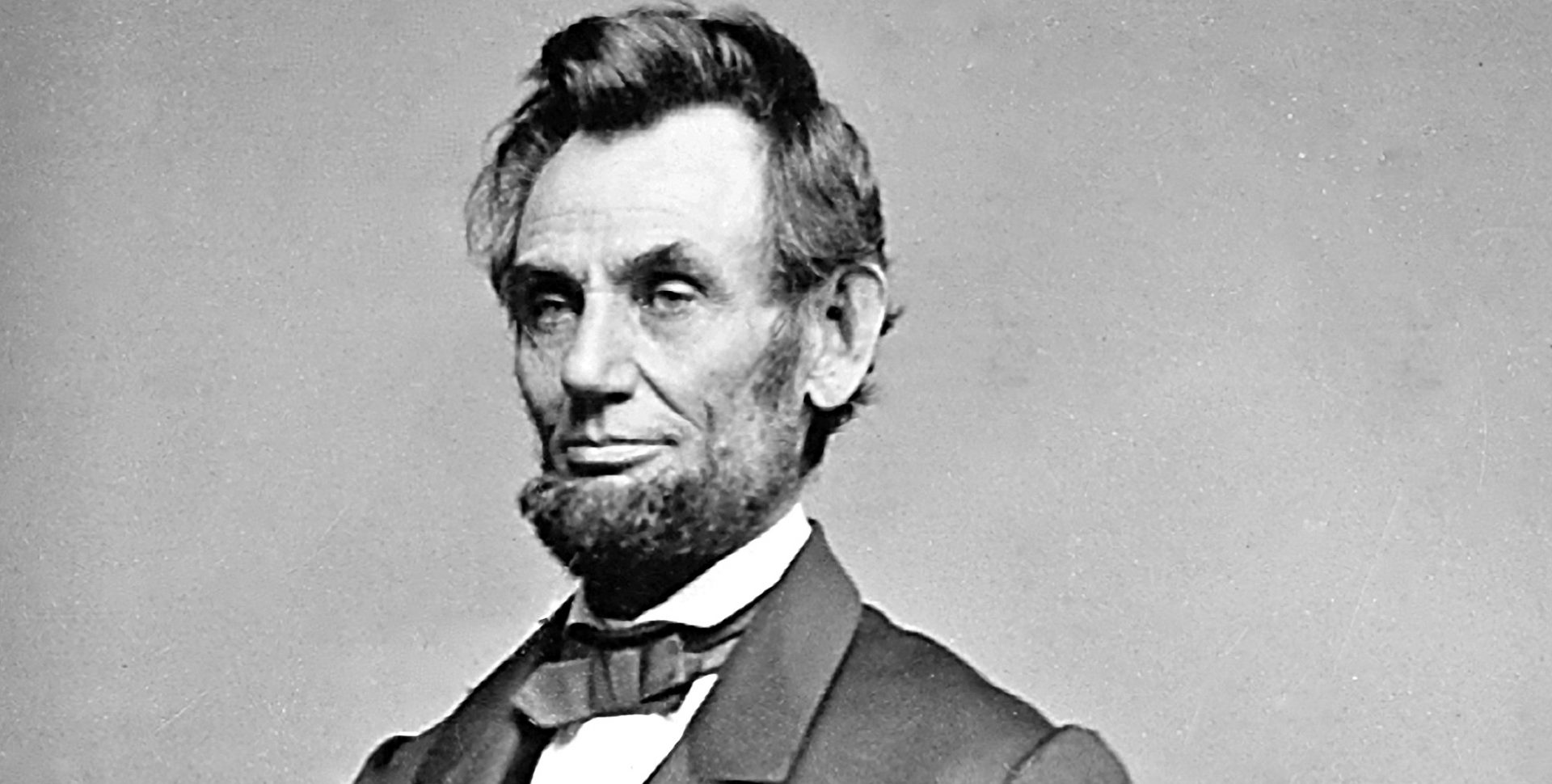

One of the best-known stories regarding Lincoln’s humility concerns his letter to General George Meade, a senior commander of the Union Army during a decisive period of the American Civil War.

After the Union victory at the Battle of Gettysburg in June 1863, in which Meade played an important role, instead of pursuing and capturing General Robert. E. Lee and his Confederate army, thereby ending the war, Meade and his colleagues gave Lee and his men the chance to flee across the river, and the war dragged on for almost two more years.

Lincoln was livid and vented to his White House staff—against Meade in particular. The news of Lincoln’s irate response quickly reached Meade and he immediately threatened to resign, defensively dismissing Lincoln’s aspersions regarding his competence.

Upon hearing of Meade’s indignant response, Lincoln sat down and wrote him a harsh letter to explain his irritation at the general’s inexplicable decision to allow Lee the opportunity to get away:

My dear general, I do not believe you appreciate the magnitude of the misfortune involved in Lee’s escape—He was within your easy grasp, and to have closed upon him would, in connection with the our other late successes, have ended the war. As it is, the war will be prolonged indefinitely… Your golden opportunity is gone, and I am distressed immeasurably because of it.

If Meade had thought about resigning before the letter, he would certainly have resigned immediately — and probably gone into exile — after he received it.

But Meade never did receive it, because Lincoln never sent it.

He waited until the following morning and then decided, on reflection, not to send the letter after all. Instead he inscribed the unsent letter, “to Gen. Meade, never sent, or signed”.

It went into filing and would not reappear for over a century.

You may be questioning: if Lincoln was that humble, surely he would have taken the letter he had written to Meade and ripped it to shreds. By preserving it in his files and noting that he had never sent it, was he not letting us know how “humble” and “restrained” he was? Where is the humility in that?

But perhaps that question is based on a false understanding of humility. INFLUNSR defines humility as choosing first to go last. We all imagine the idea of humility to mean a complete lack of ego. Nothing is about me and my opinions are not that important.

But that is not the definition of humility. That is the definition of low self-esteem.

Ego is not evil in-and-of-itself. Only when ego propels a person into narcissism and self-indulgence does it become destructive.

Self-confidence that leads one to stand up for truth is the paramount trait of good leadership, and can coexist beautifully with humility.

Because when something is for the greater good, even the most humble person can stand up for what they believe in.

Humility only becomes evident, and relevant when no purpose is served by projecting one’s ego.

When it came to the duties of the presidency, Lincoln was fierce. But when he felt the need to vent his personal frustrations, and to settle a score with a recalcitrant general, Lincoln was humble. But how would anyone learn that lesson if no one knew that Lincoln had written the letter and then not sent it?

Perhaps Lincoln wished to preserve for future generations this important lesson in humility, and what better way to do that than to file away the contentious letter he had never sent.

Humility must never be misunderstood as a lack of backbone. Rather, humility is defined by a complete disinterest in self-promotion or self-projection, unless a greater good is involved.

When approached by God to lead the Jews out of Egypt, Moses genuinely felt he was not the right person – surely there were others among the elders who were more up to the task? And so he spoke up, for the greater good.

When he realized the Jews had worshipped a golden calf, Moses genuinely felt that the Tablets were too precious for them, and so he smashed them, for the greater good.

Great questions to consider:

Do you tend to diminish or degrade yourself in front of others? Does your next generation leader tend to diminish or degrade themselves in front of others?

How can you see yourself the way Christ has made you? How can you help your next generation leader see themselves the way Christ has made she or he?

Do you understand you have something to offer others for the greater good? Does your next generation leader understand she or he has something to offer others for the greater good?