Singer-songwriter Thad Cockrell is an artist not afraid to express his emotions. His songs are personal and unguarded, laying bare his feelings about love and his place in the world. And his performances are artful in their openness, passionate without becoming histrionic. Cockrell grew up the son of an Independent Baptist pastor who also happened to be the president of Cockrell’s school. While in school, Cockrell discovered his love of country music and rock and roll, which was forbidden in his home. Cockrell’s early work found him making music steeped in country and folk, most notably 2003’s Warmth and Beauty and 2005’s Begonias (the latter a collaboration with former Whiskeytown vocalist Caitlin Cary). After stepping away from the music business, Cockrell returned as part of the indie pop duo Leagues, and with his 2020 solo effort If In Case You Feel the Same, he made a bold step into contemporary pop.

For Cockrell, one of his greatest hopes for If in Case You Feel the Same: the potential for creating an unlikely unity among those from entirely different walks of life. “One of the things I really wanted to do with this album was make a record with people who didn’t look, think, or believe like me,” says Cockrell. “I had this idea that if we created something really special, maybe it would have some kind of ripple effect—so that when we play these songs live, the people in the audience don’t all look, think, and believe the same too. To me unity comes from diversity, not from sameness, and that’s what makes things really powerful.”

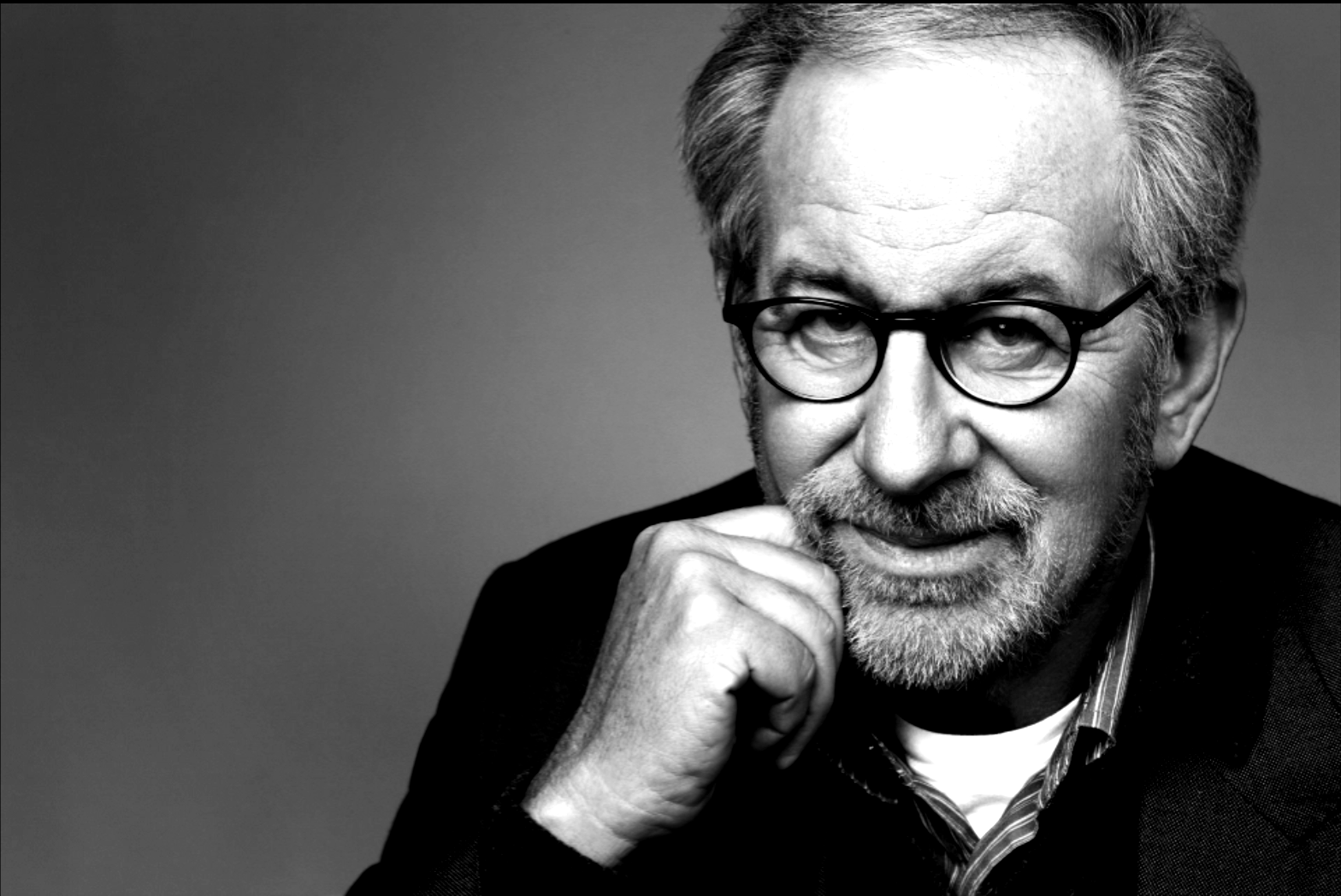

”“I dream for a living. This is what I’ve done all my life.

This is what I wanted to do with my life.”

Considered one of the founding pioneers of the New Hollywood era and one of the most popular directors and producers in film history, Steven Spielberg talks about what it takes…

Everything I’m about to tell you happened completely by accident. And I think it all started out when I was maybe six or seven years old, and my father came over to me and said, “I’m going to take you to see the greatest show on Earth.” And when you promise a six-, seven-, eight-year-old young boy that you’re about to see the greatest show on Earth, I couldn’t have been more excited.

My father explained there were going to be lion tamers and circus acts. There were going to be clowns and trapeze artists, and I was absolutely delighted, and I looked forward to this for a week. On the weekend, we got in the car. We drove to Philadelphia — we lived in New Jersey, in Haddon Township, New Jersey. We drove into Philadelphia, and it was very, very cold. It was wintertime, around the holiday season, and we stood in a very long line, I remember, against a solid, red brick wall for what seemed like hours.

I think we actually stood in line for about two-and-a-half hours. The line just inched forward. I didn’t quite understand. I was waiting to see the tent, and there was not a tent. There was a brick wall. We walked into some rather large doors, and we walked into a very — kind of a dimly lit room. I remember the room had a lot of pink and purple lights, and the ceiling looked like a church. It was a lot of Rococo carvings.

There wasn’t any kind of iconic, you know, symbology in the room, but it felt like a place of worship, a little bit like our synagogue, actually, and I still didn’t quite understand about the greatest show on Earth. And I sat down in some seats, and they were all facing forward, not bleachers but seats. There was a large red curtain — I’ll never forget this, and the curtain opened. The lights went down, and a dimly lit image came on the screen, and it was flickering, and it was kind of grainy because we were sitting way in front.

And suddenly I realized that my father had lied to me, and had betrayed me, and had taken me to a circus that wasn’t a circus. It was a movie about a circus, and I had never seen a movie before. That was the first movie I ever saw, Cecil B. DeMille’s The Greatest Show on Earth. I had never seen a motion picture before.

I had seen a lot of television because my dad was an electrical engineer, and in his spare time, when he wasn’t working for RCA, he was repairing the early television sets of the early ’50s. So I knew television, but I didn’t know movies. That was my first movie experience, and I think the feeling of disappointment and regret and betrayal lasted only about ten minutes, and then I became just one more victim of this tremendous drug called cinema, and I was no longer in a theater. I was no longer in a seat.

I wasn’t aware of the surroundings. It was no longer a church. It was a place of equal devotion and worship, however. I became part of an experience, and I became part of the lives of a lot of people that I never would meet, and I would only get to know in this one story, but that became my life. Now in the center of this movie, if any of you remember the Cecil B. DeMille film The Greatest Show on Earth, there’s a tremendous train wreck, where a train speeding along the tracks is encountered by a car, and the train hits the car.

The car flips over the top of the engine, and the train goes off the tracks, and it’s a tremendous disaster, where all the cars pile up. It was a special effect sequence. Later, I learned it was a miniature train, but it was as real as I’ve ever seen anything in my life. It was the greatest disaster I ever beheld, and for me it began my interest not in making movies but in asking my dad to get me a Lionel electric train.

So I went from wanting to become part of this incredible experience to wanting to own my first electric train, and that holiday season my dad got me my first Lionel engine and a little coal car and a caboose and a few passenger cars. And the next year, I asked for the same thing. I said, “I’d like another engine,” so I had two trains. And as I got older, I began to collect every year, more and more cars and people and semaphores and crossing signals. I became a complete electric train nut.

And I had a rather large layout in our — and by this time, by the way, we had moved from New Jersey to Phoenix, Arizona, which, by the way, when you’re about 12 years old, there is nothing to do in Phoenix, Arizona, nothing at all. So I had a lot of time on my hands, and I was really interested in seeing what it would look like if I could recreate that memory, now several years older, of The Greatest Show on Earth, and could I recreate the train wreck? And I actually took my two trains, and I just rammed them into each other, and they broke.

And I told my dad the train had broken, and he said, “How did it happen?” I said, “I rammed them into each other,” and my dad had them repaired. And the next week I crashed my trains into each other again, and the other train broke, and my dad said, “Look, you know, you — I’m going to take the train set away if you crash these things into each other one more time. You’re not going to have trains anymore.” But there was something about whatever the primal sense of wanting to destroy something because of that movie — whatever got into me, I needed to see those trains crash into each other.

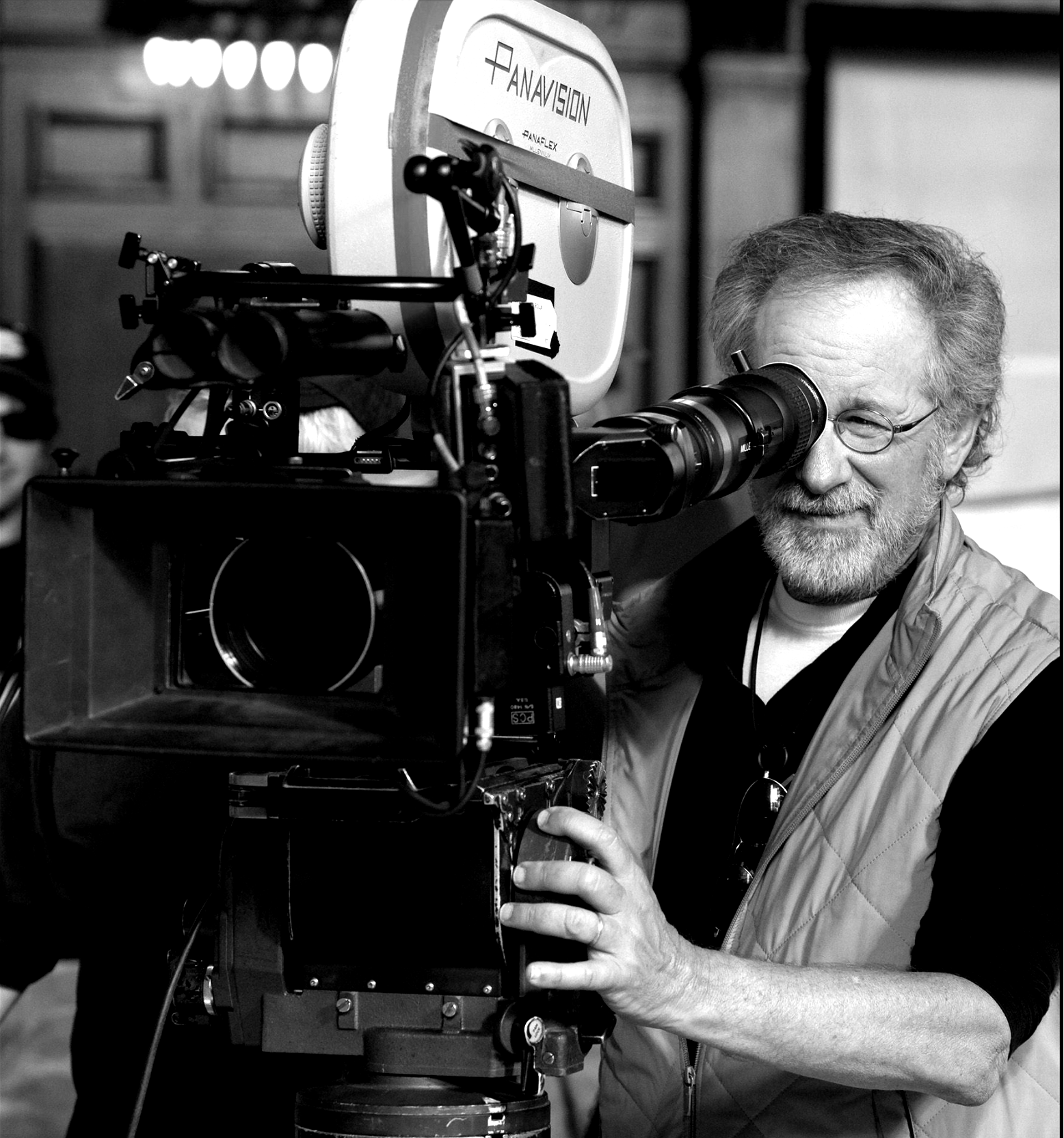

And so, I also didn’t want to lose my train set. My dad had, sitting around the house — which I always had taken for granted — this little eight millimeter Kodak film movie camera with a turret that had three lenses, kind of wide, medium, and close-up lenses. I never really bothered with the camera, but I thought, “Well, I know what I can do. What if I film the trains crashing into each other? I can just watch the film over and over and over again.”

And that’s how I made my first movie.

I shot one train, just all in the camera. I didn’t have an editing machine. I just put the camera low to the track, the way we, as children, like to put our eyes close to the toys we’re playing with so the scale seems to be, you know — the scale seems to be realistic. And I just filmed one train going left to right. I filmed the other train, cut the camera, turned it around, the other train coming right to left. And intuitively I figured out that if I put my camera in the middle and they met in the middle, I’d have my train wreck. Well, that’s exactly what I did.

Luckily the trains didn’t break, but I looked at that film over and over and over again, and then I thought, “I wonder what else I could do with this camera?” And that’s how it began, and that’s how I became a director. And the first time I sensed that an audience was kind of agreeing with my choice of profession was when I was a Boy Scout and I went out for the Photography merit badge, and I wanted to — and the requirement in the merit badge simply said you have to tell a picture with still photographs.

Our still camera broke. I went to the Scoutmaster. I said, “Can I tell a story with our home movie camera?” He said, “Yes” — to fulfill the requirements for the merit badge — and I made a little Western called Gunsmog.

I’m really dating myself because, of course, James Arness and Gunsmoke was all the rage on television in those days. And I made this little Western with my sisters and my friends, and my next-door neighbors and some of the Boy Scouts. And we just — everybody had cowboy suits because we lived in Arizona, my goodness, you know.

And so we all brought our cowboy suits out, and I made this little Western movie and showed it to the Boy Scout troop on a Friday night when we had a meeting, and they went ballistic. They were screaming and clapping and laughing both with and at the movie. I didn’t care. It was a response, and the response set me on fire. It absolutely set me on fire, and I never wanted to live without some kind of affirmation, some kind of collective feedback.

And maybe that’s why my early movies were all about you. My early movies were all soliciting you, making you my partners, thinking about you behind the camera, thinking about what would turn you on, what would get you excited, what would make you laugh, what would make you scream. How could I create suspense out of whole cloth when that darn shark never worked? And you were my partners. My audience, you know — I collaborated with you, and you collaborated with me, and I think in the beginning of my career, I had this wonderful experience, and the thing I really want to emphasize is, I didn’t have a choice. I didn’t have a choice.

When you have a dream — and the dream isn’t something you dream and then it happens, the dream is something you never knew was going to come into your life — dreams always come from behind you, not right between your eyes. It sneaks up on you. But when you have a dream, it doesn’t often come at you, screaming in your face, “This is who you are! This is what you must be for the rest of your life.” Sometimes a dream almost whispers, and I’ve always said to my kids: “The hardest thing to listen to, your instincts, your human personal intuition, always whispers. It never shouts. Very hard to hear. So you have to, every day of your lives, be ready to hear what whispers in your ear. It very rarely shouts.”

We can rejoice, too, when we run into problems and trials, for we know that they help us develop endurance. And endurance develops strength of character, and character strengthens our confident hope of salvation. Romans 5:3-4 NLT

Here is what we want to wrestle with: INFLUNSR defines grit as choosing passion over distraction. Spielberg said “… you have to, every day of your lives, be ready to hear what whispers in your ear.” What is the dream that is whispering in your ear? What will that dream require of you? Journal your thoughts.